Alexander Thomson’s St Vincent Street Church has closed, the city is selling off a Mackintosh building to save money, and Victorian gems lie empty. Glasgow’s architectural heritage is at a tipping point, writes John Stewart

Glasgow is a city in crisis once more. The immediate post-war decades brought little beyond six-lane motorways and the comprehensive redevelopment of vast tracts of the city, and yet enough survived to be appreciated in the ’80s and ’90s, when Glasgow was much restored and celebrated once more as one of our great, vibrant, regional British cities – it was a very real urban renaissance.

But those days are over. The city centre is filthy, footfall is down, visitor numbers have plunged and, having presided over this decline, the City Council – who have contributed so much to the malaise – have simply no ideas as to how to reverse the process.

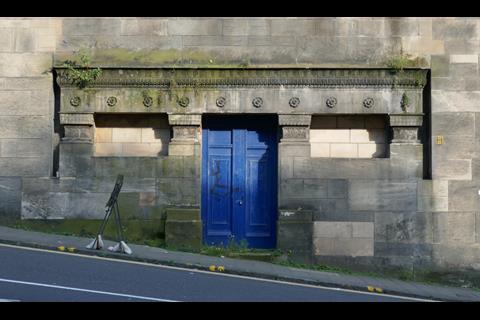

The impact on the city’s architectural heritage is quite frightening. Alexander Thomson’s only surviving church in St Vincent Street has now closed to worshippers, his Egyptian Halls remain vacant, James Salmon’s Lion Chambers is crumbling, JJ Burnet’s exquisite Savings Bank Hall lies empty and, as far as Mackintosh’s surviving buildings are concerned (having already lost his School of Art), as Stuart Robertson (the director of the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society) recently confirmed, Scotland Street School is currently closed, the Lighthouse never reopened after the pandemic, the Lady Artists Club lies vacant and, in the last couple of weeks, the City Council has put his Martyrs School on the open market. These are just the leading examples, with many, many more architecturally and historically important buildings now at risk.

It doesn’t need to be like this. The solution to this malaise is a combination of civic leadership, community action and private sector investment. Back in the 1980s and ’90s, former Lord Provost Pat Lally was the driving force behind the Glasgow Garden Festival and Glasgow’s selection as both the European City of Culture in 1990 and European City of Architecture in 1999. He and the Council revived the city centre, reversed the flow of residents out of the city and achieved what many thought impossible at the time – namely, to establish Glasgow as a visitor destination.

There have also been numerous equally successful community initiatives in the city, such as the saving of Victorian Lambhill Street School in Kinning Park, which had been used as a community facility for some years before Strathclyde Regional Council proposed its closure. This was opposed by local residents, who occupied the building 24 hours a day for 55 days before the Council finally caved in and offered the building’s users the property on a peppercorn rent. Since then, they have maintained and improved it with the help of Scottish Government grant funding, National Lottery funding and New Practice Architects.

Perhaps surprisingly, there is also no shortage of willing and sensitive private developers in Glasgow, and there have been many recent success stories, such as the rescue of James Miller’s graceful townhouse at 10 Lowther Terrace, which had lain empty for over a decade, or indeed the outstanding restoration of his suave Anchor Shipping Line Building in St Vincent Street, which now serves as a hotel, bar and restaurant. But these projects – while to be celebrated – are just drops in an ocean of decay. The private sector needs encouragement, and while local and central governments continue to talk a great talk about growth and wealth creation, they seem to spend most of their energy putting every possible new impediment in its way.

This is not just a tragedy for Glasgow but for Britain’s architectural heritage too. Glasgow is still, just, Britain’s finest Victorian city (as opined by John Betjeman, one of the founders of the Victorian Society) – and it now has a heritage crisis that needs both a local and a national response.

>> Also read: Rebuild the Mack, but why stop there?

Postscript

John Stewart is an architect, architectural historian and author. Before retiring from architectural practice, he led Jacobs’ multi-disciplinary architectural consultancy in the UK. He has written six books, including his most recent work, British Architectural Sculpture, published in May 2024 by Lund Humphries.

2 Readers' comments