AHMM director defends demolition plans

AHMM director Paul Monaghan has defended the controversial proposal to demolish all but the façade of listed Richmond House to accommodate a temporary Commons debating chamber.

By removing the floors behind the Whitehall elevation they would create a triple-height central lobby with views out to the Cenotaph that would become the “heart of Parliament”, he claimed.

“We have made the piece that most people are interested in the centrepiece of the new building,” he said, defending the proposals against criticism from opponents.

AHMM’s proposal also references elements of Whitfield’s design, he said – notably by using stock brick and playful string courses. The faceted shape of the corners was another nod – while the shape of the windows echoes those at AHMM’s Stirling Prize-winning Burntwood School in Tooting, he said.

Monaghan revealed AHMM originally planned to use red brick in deference to the Norman Shaw buildings on the Embankment, but decided they clashed.

“It felt too harsh so we went for stock brick and it became a softer, background building,” he said.

Monaghan was speaking to BD after a press conference at which the first images of the proposals for the temporary House of Commons and wider Northern Estate were unveiled – an estimated £1.6bn part of the wider £4bn restoration and renewal of Parliament.

These showed how AHMM and BDP – the architect working on everything but Richmond House – propose to create a Commons campus by restoring and linking half a dozen buildings which date from different eras and were created for varied uses in different styles. This has involved some complex “twisting and weaving” and 18 months of thought, he said.

While Richmond House will be almost entirely rebuilt, other parts of the estate will be restored by conservationists and converted into modern office accommodation.

The brief required not just a debating chamber for the estimated seven years it will take to renovate Parliament but division lobbies, committee rooms, MPs’ offices and public facilities – all within an eight-minute walk from the chamber for when the division bells sounds.

The proposals include an energy centre beneath Richmond House – which is much bigger than the narrow Whitehall elevation suggests – part of a three-level basement in which bins, bikes and plant can be concealed.

This will allow the spaces between buildings to be turned into attractive public realm, said BDP’s architectural director Alasdair Travers, albeit only accessible to those with security clearance.

BDP’s proposals will also see a glass roof installed over the courtyard at grade I-listed Norman Shaw North. A historic alley running parallel to Whitehall – Canon Row – will be revived to create a “street” through the scheme and an entrance for MPs.

The public entrance will be via a temporary security pavilion outside Richmond House’s current entrance, protected by demountable bollards and a widened pavement (at the expense of one lane of four-lane Whitehall).

The pavilion and bollards will go once MPs have returned to the Palace of Westminster, but the legacy of the temporary Commons chamber is still under debate. Possible future uses include an education centre or a Parliamentary archive – or a back-up chamber in the event of an emergency.

“In the next 10 years the whole Northern Estate will be future-proofed for the next 100-odd years,” said Monaghan. “It hasn’t had money spent on it for 50 years.”

AHMM won the job three years ago through its partnership with contractor Lendlease, but its successful work on neighbouring Scotland Yard helped build confidence that it could handle historic buildings and serious security issues, he said.

“It’s very exciting but very challenging. You feel a huge weight of responsibility designing this,” he admitted.

For the first 18 months they looked at whether they could keep Richmond House but eventually ruled this out. Whitfield’s celebrated staircases are too narrow for an assembly building, for one thing, he said. Whitfield, who was also the architect of Paternoster Square and oversaw the restoration of Christ Church Spitalfields, died in March. He and his partner Andrew Lockwood were not happy about sacrificing their grade II* building.

Other options – including Norman Foster’s proposal for twin chambers on Horse Guards Parade and Michael Hopkins’ proposal to put the Commons chamber in the atrium of his practice’s Portcullis House were also dismissed.

The Portcullis House idea – backed by campaigners at Save which called the loss of Richmond House “state-sponsored vandalism” – couldn’t accommodate all MPs let alone the other uses; would involve dragging a ninth building into the construction project; and would see MPs sitting over a public Tube station, with the attendant security risks.

A planning application is due to be submitted later this year, with consent expected before Christmas. The work is predicted to take until the mid-2020s, after which the five- to eight-year restoration and renewal of Parliament can begin.

A concept design for that is two years away, while a planning application for the remodelling of Powell & Moya’s QEII conference centre into a home for the Lords is about a year away. Both are being undertaken by BDP.

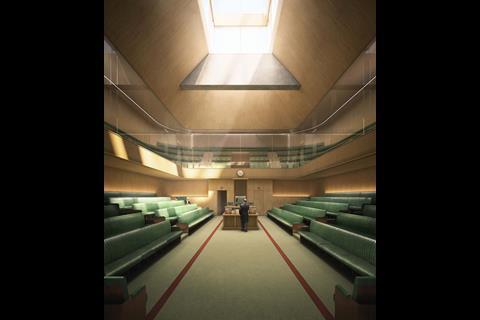

>> Also read: First look: AHMM’s temporary Commons chamber

>> Also read: Architect attacks MPs for dismissing ‘houseboat of Commons’ plan

>> Also read: BDP’s Parliament refurb will not become a ‘money pit’, MPs told

10 Readers' comments