Ben Flatman examines how architect and artist Karl Singporewala weaves architecture, heritage and personal memory into a rich body of work shaped by Parsi diasporic experience

Cosmos, Memory, Scale is the inaugural exhibition of the new artist in residence fellowship at the Shapoorji Pallonji Institute of Zoroastrian Studies at SOAS, and it sets a high bar for what this programme can achieve. It brings together more than 15 years of work by Karl Singporewala, an artist and architect whose practice moves fluently between the two disciplines.

The exhibition takes place in the large basement galleries of the SOAS Gallery in Bloomsbury, formerly the Brunei Gallery and designed by Nicholas Hare Architects.

Singporewala trained as an architect and has worked at Ian Ritchie Architects and Barbara Weiss Architects, and now runs his own practice (Karl Singporewala + the design bureau). His experiences as an architect remain visible across the exhibition in his approach to structure, precision and scale. His artworks can often be interpreted as architectural studies or models of imagined structures.

He is adept at digital manufacturing. Pieces are laser cut, photo etched or 3D printed, using techniques that he has long applied in practice. The link between design and artwork runs in both directions.

His architectural sensibility finds its way into his sculpture, and his sculptural instincts appear again in recent public commissions, including the large-scale Keki’s fusion (2025), which was fabricated and installed earlier this year with Cake Industries. This public commission is represented in the exhibition with a large C-Type photograph taken in twilight by Judith Jones RWA.

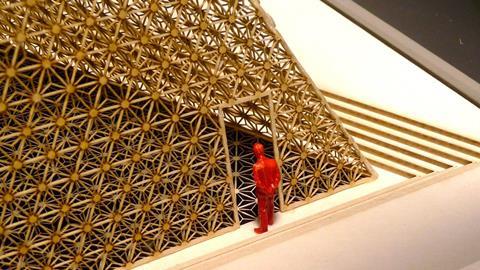

One of the most striking qualities of the exhibition is the shift in scale across the rooms. Many of the early works are small, intricate and held within their own internal systems of geometry. Nearby, recent works move decisively into the monumental, with boldly coloured timber pieces that stand at human height.

He uses architectural scale figures in several works, which subtly adjust the reading of abstract forms into mock-ups for monuments or public artworks. Even the entirely abstract pieces gain a sense of inhabitable volume once a figure is introduced. It is a neat device and constant provocation to interpret the work at a variety of scales and distances.

The exhibition opens with or in the dream of a dream (from 2024), a tall lamp-post-like structure placed at the threshold of the gallery. It draws openly on the lamp-post in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe while folding in memories of Tower Bridge and the artist’s relationship to fatherhood.

It is a work about anchoring oneself in stories and place. As a threshold piece, it sets the tone for an exhibition concerned with orientation, both physical and cultural.

Orientation is central to Singporewala’s engagement with his Parsi Zoroastrian heritage. Zoroastrianism’s origins lie in ancient Persia, yet the defining story of the community in modern times is that of diaspora. After the Arab Islamic conquest of Persia, many Zoroastrians settled in India, where Parsi communities grew and developed distinctive cultural practices.

Today the Parsi population in India is in steep decline and the culture and its traditions face an uncertain future. Singporewala notes that “there are more registered architects in the UK than there are Parsis left in Bombay”. This sense of fragility underpins much of Singporewala’s work. His art is not nostalgic, nor exactly devotional, but it is attentive to the material forms that hold and transmit cultural memory.

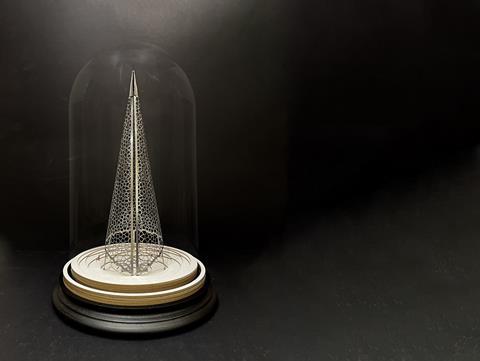

This attention is clearest in his repeated return to the ses, the ritual tray found in many Parsi homes, and the four vessels it contains. The soparo, the most striking of these, is a tall conical container for sugar which symbolises the cosmic mountain of sweetness.

In domestic settings it may be modest, even left empty, but in Singporewala’s hands it becomes the basis for dramatic formal invention. His monumental Soparo (2025) in the Lighthouses series transforms this domestic vessel into a tower-like structure. The form is both playful and reverent. It takes a familiar ritual object and renders it large enough to walk around, shifting it from the scale of the hand to that of the city.

The play with scale continues elsewhere in the show. Follow me, follow me (2025) takes the form of a large yellow stellated star, its interlocking geometry drawing on cosmological ideas while encouraging viewers to move around it and read it from multiple positions. Nearby sit intricate maquettes in brass, paper and plastic.

The exhibition also includes historic and personal items drawn from SOAS collections and from the Singporewala family. Several generations of the family ses sit in a case, silver trays holding the soparo, pigani, divo and gulabdan. They offer something the artworks cannot supply by themselves, a direct material link to the domestic setting from which these forms originate.

One of the most compelling works, The last tower of silence, which was originally exhibited in the architecture room at the RA Summer Exhibition from 2011, reimagines a traditional funerary structure as a contemporary high-rise. In Zoroastrian practice the Tower of Silence is a circular structure used to expose the dead to carrion birds, a ritual that protects the purity of earth and fire.

Singporewala’s version is vertical, almost corporate in silhouette. It is an uneasy reflection on the conditions of diasporic life, where inherited practices can become distant and at risk of fading. The exhibition catalogue notes that the piece responds to ‘ancestral practices that risk being obscured or lost in hybridised, multicultural contexts such as London’.

A recurring motif in the exhibition is the object under the bell jar. Several works appear encased or framed as if specimens. It is difficult not to read this as an echo of the Victorian impulse to classify and catalogue. In Singporewala’s hands, though, the specimens are fragments of a living tradition presented in a way that highlights both their specificity and their vulnerability.

Cosmos, Memory, Scale is an exhibition about heritage and loss, but also about what it means to work with forms that are inherited. Each of the 35 pieces on display is layered with personal stories from his architectural career and juxtaposing life events. It also explores the role of the architect as both maker and interpreter.

In the end, what stays with the viewer is the clarity of Singporewala’s approach – thoughtful, technically precise and rooted in an ongoing attempt to understand how memory survives through objects and through the stories we tell about them.

>> Also read: Not all artists are architects, but all architects are artists

>> Also read: Encounterism: The Neglected Joys of Being In Person

Postscript

Karl Singporewala: Cosmos, Memory, Scale is at the SOAS Gallery until 13 December 2025.

Ben Flatman is an architect, planner and freelance writer. He was until recently BD’s architectural editor

No comments yet