Jenny Marris reviews a new book on the architecture that defined an era

Love them or loathe them, brutalist buildings seem at last to be having something of a renaissance in the consciousness of those interested in our built environment. Whatever your feelings about the mass and edginess of many buildings of the 1960s and 1970s, they are a significant part of our heritage and need to be appreciated for their place in history and the times they represent, even if their aesthetic qualities are not to your taste.

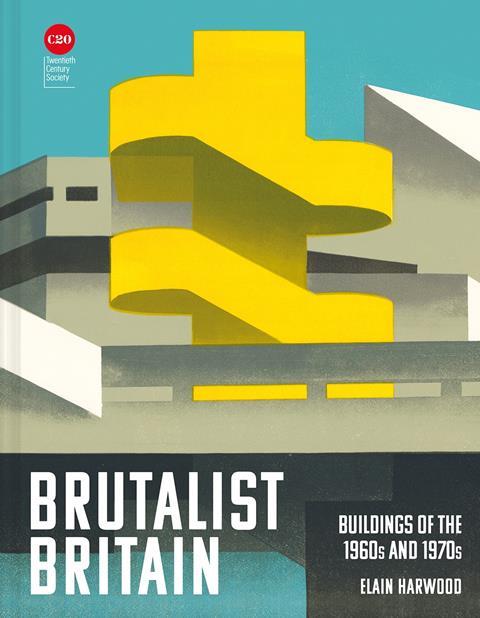

Elain Harwood’s Brutalist Britain: Buildings of the 1960s and 1970s is a fitting addition to her series on twentieth century architecture. With its comprehensive introduction and mass of stunning photographs, the book clearly demonstrates that attitudes to brutalist architecture have finally moved on from the ‘carbuncle’ views of earlier decades.

The last few years have seen a distinct shift in attitude with a new awareness on the part of institutions like Historic England and the National Trust. The publication of several important books on post-war architecture and the emergence of a generation seeing these buildings with new eyes has also helped change perceptions.

Sadly, it is already too late for far too many of the most exciting of our brutalist buildings

Those of us born into a world of modernist architecture have taken it for granted for far too long. It is only now, with the threat of demolition all around us, that we can see the importance of what it is we are losing. Sadly, it is already too late for far too many of the most exciting of our brutalist buildings.

Public buildings and social housing that have been neglected for decades make an easy target for the concrete cruncher, but none of us has the right to delete this vibrant period from our architectural history, with its new technology, democratic ideas and multiple international influences. Nor is it appropriate to ignore the enormous environmental cost of demolition and rebuild.

Architects, planners and developers have a responsibility to see outside the constraining box of demolition and to explore imaginatively the possibilities for repurposing and retrofitting in a way that pays homage to the original designs. What Harwood offers here is both a clear statement of the historical importance of these buildings and a fresh insight, supported by some excellent photography, into their aesthetic qualities.

In the comprehensive coverage of her introduction, Harwood doesn’t shy away from the difficulties of defining brutalism. She manages to make complexity an acceptable way to understand the different influences at play, and the different ways in which developers and architects made use of the new technologies and ideas of the time.

She explores the social and political context within which the ideas behind seminal buildings like Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation and the work of the Smithsons emerged. It is an introduction dense with intriguing facts and useful references for those who might wish to explore further, set within the framework of the brief history of brutalism as a particular phase of modernism, all written in Harwood’s lively and accessible style.

It seems to me that brutalist buildings get labelled as such because certain elements, such as the use of concrete or a lack of ornamentation, are seen to have been given primacy in the design, while other details, if given due attention, are less likely to justify the label brutalist. To what extent, for example, is Birmingham’s threatened Ringway Centre, featured in Harwood’s book, seen as brutalist because its external surface is concrete?

The appeal of a book like Brutalist Britain is that it also demands that you pay attention to the details

In fact, the architect, James Roberts, designed it to be finished in Portland stone. While its mass, a sweep of 230 metres along Smallbrook Queensway, might be seen to be influenced by Le Corbusier, the uplighters and decorative panels added ornamentation that John Grindrod in his recent Radio 4 Front Row interview suggested put the Ringway Centre ‘on the cusp of being brutalist’.

The appeal of a book like Brutalist Britain is that it also demands that you pay attention to the details. Brutalist has become a shorthand description for a wide range of buildings consisting of different stylistic elements, as these photographs demonstrate. As a label it is useful for quick reference and it is to be hoped in the new era of appreciation for these buildings it will lose its negative connotations.

The bulk of Harwood’s book is taken up with individual photographs of particular buildings, each accompanied by a brief informative paragraph. The photographs present the buildings at their very best, many taken from angles which emphasise the sculptural drama of their design and their brutalist credentials, highlighting the shapes and textures made possible by the use of concrete in their construction.

As Harwood points out in her introduction: ‘unlike expensive steel and inflexible brickwork, concrete could be pushed into almost any shape and size thanks to reinforcement and formwork’ and ‘Sand or pebble aggregates offered infinite variations in colours and textures, sparkling where a sliver of mica or a grainy texture caught the low British sunlight’.

The book is structured on a thematic basis, so the buildings featured are grouped according to type. This gives the reader the opportunity to compare like with like and to appreciate the different ways in which architects solved similar problems, like the density required of public housing or the particular demands of sporting venues.

In terms of the sculptural, aesthetic qualities of the buildings, the photographs expose, in my view, how much more successful this architecture is for some types of building and/or context than for others. For example, I find the sculptural mass of the public housing designs more satisfying aesthetically than the buildings illustrated in the section on Shops, Markets and Town Centres.

What is most clearly on show in Brutalist Britain is the very broad canvas of brutalism

This is chiefly because they are set in a landscaped space allowing for a comprehensive view, where town centre buildings jostle with their neighbours for attention and much of their sculptural quality can not be appreciated. While the thematic groups make for interesting comparisons, and the index is invaluable, it is frustrating that there is no means of geographically locating unfamiliar buildings from different groups.

What is most clearly on show in Brutalist Britain is the very broad canvas of brutalism. The book’s strength lies in the discoveries to be made in Harwood’s detailed and invitingly written introduction and the sheer pleasure of browsing through such an interesting and well organised set of photographs. That each photograph is accompanied by what is often a quirky observation is simply an added bonus.

Postscript

Brutalist Britain: Buildings of the 1960s and 1970s by Elain Harwood is published by Batsford

Jenny Marris is a founding member of The Brutiful Action Group and a co-author of Birmingham: The Brutiful Years

3 Readers' comments