Architectural activist, teacher and campaigner Jos Boys has spent decades questioning who architecture is really for. In this profile, Mary Richardson explores how her latest work reframes access as a political, creative and collaborative practice

Architectural activist and educator Jos Boys has spent her career challenging the architectural mainstream. As a co-founder of the radical feminist design co-operative Matrix in the 1980s, she helped to expose how the built environment routinely ignored and excluded women’s needs and experiences. Decades on, Boys remains one of the profession’s most original and persistent agitators – now focusing her energies on rethinking how we design with and for disabled people.

Her work today, through the DisOrdinary Architecture Project, is pushing the profession to move beyond minimal compliance and instead embrace a richer, more inclusive design culture. At a time when one in four people in the UK is classed as disabled, and as our population ages, the need for such work has never been more urgent.

When we meet her, Boys is not especially keen to dwell on the past. Despite her status as a pioneering voice in feminist architecture, she is focused firmly on the present, and on the radical potential of disability-led design.

“We want to find strategies and methods to open up much more creative and enjoyable – and it’s very important that they are enjoyable – conversations around disability,” she says.

Matrix and early career

Still, to understand the force of her current work, it helps to trace the path that brought her here. Few people have played such a sustained role in asking architecture to pay attention to those excluded from its norms, particularly the able-bodied male default still reflected in much of architectural education and practice.

According to the latest ARB figures, 88% of registered architects self-report as having no disability; 3% say they have a disability; and 9% prefer not to say, while 64% are male.

Boys studied at The Bartlett and began her career as a reporter at Building Design. She went on to teach at the AA and what was then North London Polytechnic, and to conduct research for the GLC focused on gender and the built environment.

Her political commitments soon drew her into feminist and community organising – from squatting in Covent Garden to working for the Women’s Design Service, which conducted early research into topics such as women’s toilets, and making public spaces safer for women.

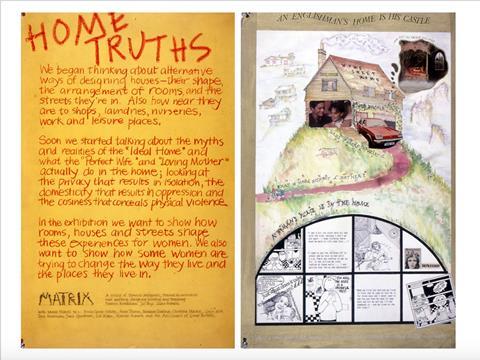

In 1981, Boys was one of the founders of the hugely influential feminist design cooperative Matrix. Matrix was run by and for women and it experimented with new ways of working, such as co-design, which have subsequently become mainstream.

Notable achievements included groundbreaking research into gender and space, published as the book Making Space in 1984. Matrix also produced feminist design guidance, seeking to introduce innovation into building typologies that had been overlooked by a male-dominated profession, such as women’s centres and nurseries.

The group supported women from under-represented groups to get into construction and architecture and it delivered finished builds designed with and for women. Boys has since worked to ensure that Matrix’s legacy is recognised, helping to digitise its archive and co-curating a 2021 exhibition at The Barbican about the group.

After Matrix, and as a single parent, she spent time as a studio tutor and teacher of history and theory at several universities. Then, in 2007, came a turning point. She met Zoe Partington – a veteran of disability-rights campaigns and well-established member of the disability arts scene – and, as Boys puts it, “over a coffee and a rant”, they found common ground in their dissatisfaction with the current state of accessible design.

“Although we now have functional access [in the built environment] – or attempts at it, at least – things haven’t really moved on beyond that,” Boys explains. “The campaigning that created the 2010 Equality Act and those ways of thinking about access have become embedded in architectural and built environment practice as part M, and in access forums and things like that. But we’ve got stuck there.”

The two women were clear that this approach was no longer working, and that there had to be a better way. And so DisOrdinary Architecture was born.

DisOrdinary Architecture

From that initial conversation between Boys and Partington grew an informal platform working project by project, exploring new, creative ways to approach inclusion and access. Drawing on contemporary art practice, the work starts from the social model of disability – a framework that distinguishes between impairment (physical, sensory or cognitive differences) and disability (the social barriers created by design, policy and attitude). It asserts that responsibility for removing those barriers lies with society as a whole.

DisOrdinary Architecture began by working with architecture students, aiming to shift mindsets among those entering the profession. “We’re against those simulation exercises where, if you are a non-disabled person, you go around in a wheelchair for a bit, or you put a blindfold on,” says Boys. “They just produce a sense of loss and fear. Instead, we run workshops designed to show people that there are many different ways of occupying and moving through space.”

A provocative intervention at the Theaterformen Festival in Braunschweig, Germany, saw the DisOrdinary team convert bike racks into seating using simple wooden seats placed on top of the racks: controversial stuff in our cyclophilic times. The idea was not just to challenge the lack of public seating locally, but also to comment on the way society values fast-moving bodies over slower ones.

They also created a Deaf Space pavilion for the festival with Deaf architects Richard Dougherty and Chris Laing.

Boys and Partington collaborate regularly with high-profile disabled artists. They are also supported by a DisOrdinary Architecture advisory board that includes some of the most influential young voices in the world of disability and architecture, such Jordan Whitewood-Neal and James Zatka-Haas of the Dis Collective, neurodivergent designer Natasha Trotman, and Poppy Levison, who is blind and studying for her part II exams at the RCA.

Through her work with DisOrdinary, Boys has become an expert in the field, writing and co-editing several definitive books on disability and the built environment, including Doing Disability Differently, Disability, Space, Architecture and Neurodivergence and Architecture. She is also just completing three years as a guest professor at the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen, and is an Honorary Associate Professor at the Knowledge Lab UCL.

Access ecologies and mapping

Rather than accepting standard definitions, DisOrdinary challenges the reductive ways disability is often framed in design discourse. “There remain huge problems with the way disabled people are put into functional categories.

“You know: ‘You’re blind’, ‘You’re deaf’, or ‘You use a wheelchair’; and there’s also an assumption that these categories are somehow very straightforward and unproblematic; not related to one another; and have no overlap. You design for ‘normals’, then at the end of the design process you add in little bits and pieces for all the people you’ve left out. Which is very odd when you think about it.”

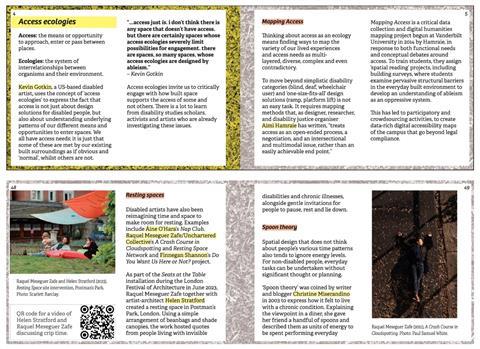

Instead, DisOrdinary draws on the idea of “access ecologies”, a term developed by disabled artist Kevin Gotkin. “Everyone has access needs,” says Boys, “it’s just that non-disabled people don’t recognise that ‘normal’ built surroundings already meet their needs.”

The aim is to record the complexity of real access needs – layered, contradictory, and often non-binary – in ways that challenge the limitations of compliance-led frameworks like part M. “Thinking about access as an ecology means finding ways to map the reality of our lived experiences and access needs [which are] multi-layered, diverse, complex and even contradictory.”

Boys explains: “Access mapping goes beyond a simple accessibility audit. It’s more of a chance to ask questions like: What were the design intentions? Which kinds of bodies and minds have these valued and prioritised, and which are marginalised or ignored? How are different people affected by their lived experience of particular spaces – what ‘ables’ or disables them?”

Rather than focusing only on new buildings, she explains: “We start by looking at existing buildings because: why wouldn’t you?” This means exploring how they came to be, how they’re used, and how people engage with them.

“That makes it very concrete,” she says. “We map what we find onto building plans and use other techniques that are as accessible as possible. And then, rather than a simplistic design solution, that becomes a body of complex, nuanced and layered knowledge out of which design can grow.”

Case studies and collaborations

The DisOrdinary access audits are intended to be positive and constructive. “Rather than a catalogue of ‘Oh, this isn’t accessible and that’s not either’, it’s more about asking, ‘What were the design decisions? What were the intentions? What kinds of concepts do architects use?’” says Boys.

Working alongside architects and mixed groups of of people with different disabilities and some with none, the goal is open discussion. “People talk about what’s accessible; what’s not; what they like; what they don’t like. It’s meant to be fun, to capture the richness of our bio- and neuro-diversity.”

They use a large enough group of participants to ensure that no one becomes somehow representative of all people with a particular disability – and to make for a good discussion. “We want a large enough group to give variety and difference, not just around impairment, but around personality and lived experience, too.”

The discussion is filmed and recorded: “The recordings form a kind of database. What you get is lots of comments, no single definitive answer. It’s really just saying, ‘People said that, this and this. You’re the designer, you work out what you’re gonna do with that.’”

DisOrdinary has increasingly been invited to collaborate with major practices. “We worked with people at Heatherwick Studio over several years,” Boys says.

“In 2024 this included a walk-and-talk audit at Coal Drops Yard. The job architect explained how they wanted to activate the space with cafés and things spilling into the walkway. We had a really interesting conversation about who it was being activated for.”

That design intent, she explains, did not serve everyone. “Loud, noisy spaces may not work for neurodiverse people or those who are partially deaf. You also can’t navigate it easily if you’re blind or partially sighted and use a white cane, as there are no clear edges or tactile demarcations to follow. So, we co-explored what an inclusive activation might be like.”

This kind of work is designed to be open-ended – to surface where different disabled people’s needs converge and where they diverge. “You look for alignments and tensions. It’s not about being deliberately complicating, just about bringing in the nuances of real life,” says Boys.

“Even different wheelchair users have different requirements, in terms of, say, accessible toilets. Lots of accessible toilets don’t even work for many wheelchair users.”

Similarly, she points out, ramps that zig-zag through steps maybe helpful for people who use wheelchairs, but can be very dangerous for people with a visual impairment. They can also be a problem for anyone with a mobility impairment who relies on handrails for support. Meanwhile, hard surfaces in public spaces can be acoustically very challenging for many people.

And, to take another example, even among people who are neurodivergent, there are big differences between where people are overwhelmed or not – in terms of what reaches them or affects them. Boys says, “So, it’s not even like you can just say, ‘Oh, you just need calm spaces.’ That just highlights the complexity.

“Things that support access for some can actually make things harder for others,” she continues. “A good starting point is to look for where there are alignments.” She gives the example of deaf signers. “If you sign and you’re talking as you’re walking, you’ll often have a third person with you who’s there informally to make sure that none of you bump into things.

“That means you might be walking three abreast, so you’d need spacious corridors. And a ramp is much better than stairs in that case. So, for wheelchair users and people who sign, there’s a lot of overlap.”

But, she adds, “there are many other people – who use a cane maybe or who have a different kind of mobility problem – for whom a ramp is actually a pain in the butt. So, it’s about looking for alignment, but also recognising multiplicity. And, ultimately, it’s about offering a variety of different ways of being able to engage with a space.”

This idea of variety runs through DisOrdinary’s work. “It’s about building in multiplicity and generosity,” says Boys. “But that is, of course, quite a political thing. And we know many architects don’t actually have huge control over that, or over their clients.

“On the other hand, we also know that we have a value system that assumes you should only use standard disabled toilets because that’s cheaper – and that you can’t have lots of variations. And to that, we’d say, ‘Well, why can’t you have lots of variations?’”

She’s quick to point out the contradictions in these norms. “That same value system finds the money for huge atrium foyers, even though they cost a lot – because they are the ‘in thing’. But nobody says anything about that.”

DisOrdinary has also begun collaborating with Foster + Partners on a series of inclusive design guides. “It’s very exciting and they have been fantastic,” says Boys. “They’re committed at the highest levels. We told them we wanted to work with people who were sufficiently senior to be able to make change happen based on what we discovered together.”

With Foster + Partners EDI team, DisOrdinary Architecture is bringing together about 18 disabled creatives to visit and engage with different buildings by the practice.

Design as disruption

Whilst the primary aim of most access consultancy is to enable more inclusive built spaces, for Boys there is a deeper intention–- to challenge underlying normative practices and processes across architectural education and the profession. Starting from disability and difference, she believes, is a ‘creative generator’, and can help designers to challenge norms.

“It’s not like you have to start at the beginning of a design project and include absolutely everybody. It’s more that thinking about different sorts of bodies and minds first actually helps you think in a much more creative way. It gives you some creative juice. It helps you think about how you might design things a bit differently – it helps you see where you’re doing things in a conventional way.”

This approach is sometimes called the affirmative model of design. Rather than viewing impairment solely as a deficit, it values disability as a source of strength, creativity and insight. It challenges the dominant “tragedy” model of disability and reframes it as a valuable aspect of human diversity.

Mandy Redvers-Rowe, theatre director, writer and regular DisOrdinary collaborator, puts it like this: “I’m passionate about seeing inclusive design as a creative opportunity, not a restriction.

“I am interested in how beauty is added, keen that any artistic addition enhances the experience for all visitors. Such features should stimulate all of our senses, not just rely on vision. So, when considering design, I want a building that is beautiful that as a blind person I can experience in some rich way.”

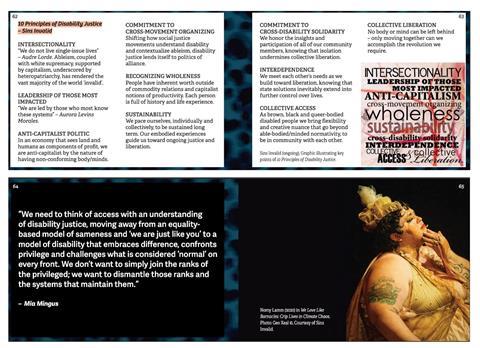

Boys also draws on more recent thinking from disability scholars and activists like Alison Kafer, Mia Mingus and Aimi Hamraie, who extend the social model into more relational terrain. In this view, disability isn’t fixed, but context-dependent – shaped by the intersection of different bodies, minds and spaces. “In the widest sense, questions of access are political,” Boys says. “They’re shaped by value systems about who matters and who is seen as unimportant, valueless, or even seen as less than human.”

As a result, explains Boys, “Some disability activists who want to centre power and inequality now talk less about access and inclusion and more about disability justice.”

Education and the future of the profession

The evening after we talked, Boys was heading off to sit on a panel at an event called Crip Climates. “As part of a retrofit, you go into a building and do a sustainability audit. Well, why can’t you do an access audit at the same time?” she suggests.

“I’d argue that the kind of adaptive, small-scale interventions that suit retrofit are actually also the best way to think about accessibility too. It’s also adaptive. Accepting that a building is never finished, that you’ll never get it ‘right’, building in maintenance and care… these things work really well in terms of accessibility too.”

She cites the Ed Roberts Campus in Berkeley, California, designed by Leddy Maytum Stacy. The building was created as an inclusive hub for organisations run by and for disabled people, rooted in the activism of 1960s and 70s wheelchair users. But, as new generations arrived – including neurodivergent people and those with environmental sensitivities – it no longer met everyone’s needs.

Rather than rebuild, they adapted: adding screens, switching to hypoallergenic cleaning products, and tweaking the space. “For me, the lesson of that is that we don’t need a huge f*ck-off building that’s perfectly accessible,” says Boys. “We need responsive processes and practices whereby things are changed and adapted.”

The DisOrdinary Architecture Project is also working to dismantle barriers faced by disabled students and professionals. “DisOrdinary events have become a safe space,” says Boys. “Quite a lot of people – disabled architecture students and practitioners – disclose themselves to us.

“They may not have told their tutors or their bosses, because that can still be an unsafe thing to do. It can really affect your possible study and career opportunities. But they tell us.”

She does find, however, that young people entering the profession are more vocal about refusing to be sidelined by ableist attitudes. She says, “The new generations of students and architects coming through are interested in campaigning within the discipline much more directly. We’re beginning to meet a much larger number of disabled people within the sector, and they’re now doing this kind of work in their own right.

“It’s not like there haven’t been disabled architects in the past, but they tended to be channelled into access consultancy – and have often done that really, really well. But younger people coming through aren’t going to be pigeonholed.”

And that is surely something that bodes well for the future of placemaking and building design – for every body’s sake.

That shift is also reflected in one of DisOrdinary’s most compelling outputs: Many More Parts Than M!: Reimagining Disability, Inclusion and Access Beyond Compliance. Highly recommended, it’s a rich resource filled with thought-provoking activities and prompts for further reading, designed to prod the sector into moving out of its comfort zone and beyond the narrow confines of regulatory compliance. Go and download it now.

It’s a fitting title for a project – and a career – that has consistently argued for more: more imagination, more generosity, more voices in the room. Jos Boys has spent decades showing how architecture could be different. The profession would do well to keep listening.

>> Also read: Why inclusive housing design benefits us all

>> Also read: Why building inclusion should be seen as a professional obligation

Postscript

The DisOrdinary Architecture Project is 18 years old this year and will be hosting a birthday celebration at the Zaha Hadid Foundation this evening (17 June), from 6-8pm, as part of the London Festival of Architecture. Free tickets available on Eventbrite.

No comments yet