British ‘regeneration schemes’ could learn a lot from the Clamart Panorama brownfield development near Paris, says Nicholas Boys Smith – above all the humility to ask people what they really like

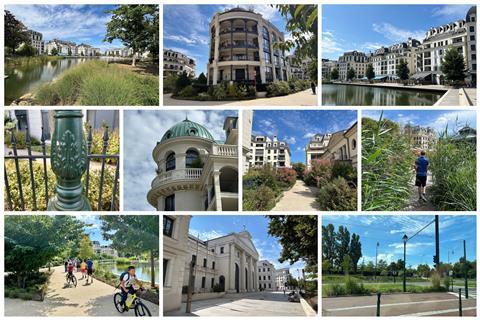

Clamart Panorama: gentle density circling around a walkable and tree-lined lake

Come with me to Clamart, seven miles from Paris. Here is regenerative development in reality not in name.

Up and down Britain, councils, landowners and public bodies write vision statements, talk of regeneration, pay overpriced consultants and architecture firms to create top-down master plans. They perform quasimendacious community engagements which ask every question, apart from the most important one: what places do people like and why.

They plant trees (this is a good thing) but, too often, and apart from rare exceptions such as Lichfield District Council, they don’t actually create places which tally with the increasingly confident evidence on what places prosper and why. They don’t actually ask where people like to be, they don’t actually look at the proper evidence on patterns of land value and prosperity. If they did, they would do something different.

It is better urban regeneration than anything done in the UK in my or my parents’ lifetimes

So come with me to Clamart Panorama, on a former industrial site and a metro and tram ride out of Paris. See what we could and should be doing instead: urban regeneration carried out by a public body that dared to listen not just to the experts but really to the people. It is better urban regeneration than anything done in the UK in my or my parents’ lifetimes.

Take the Métro line 13 from Paris to Châtillon–Montrouge. Then take the grass-lined tram T6 toward Viroflay. Get off at Division Leclerc. Head for the Parisian mansions in front of you.

Quickly you will start finding the patterns that emerge in theoretical work such as Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language and Jane Jacobs’s Death and Life of Great America Cities as well as Create Streets’s own empirical research into the relationships between place with value, happiness and prosperity. Most are visible within this 14ha site.

First of all, we have gentle density: mansion blocks of five, six or seven storeys, creating a lot of new homes within a walkable carapace: lots of people to shop, work or walk or jump on the tram to Paris. But no need for towers or dehumanising groundscrapers.

Secondly, they have put a lake in the middle of it. This is the “Panorama” the French estate agents are marketing. This is perhaps not a trick you can pull off anywhere, but it always surprises me how little we run rills or canals or streams through regeneration programmes.

In my study, Beyond Location, on the correlations between urban design with value, little comes out more clearly than that a view over water adds monetary value: between 18 and 90% in studies of lakes.

This value is profit. But it can also be converted into social housing or better amenities and more beautiful buildings. More makes more. In Clamart, more than half the apartments look out on a luscious and lovely lake, lined with trees and bull rushes.

Thirdly, we have biomorphic forms mirroring nature. We have curves and sinuous shapes at every scale: in the details, in the buildings and in the town. Leaves and acorns hang from windowsills and corners; roofs curve in domes or mansards, streets wind out or around the lake. Shapes which echo nature are more popular and reassuring for most of us.

Fourth, this is a good place to walk. A tight network of well-enclosed and walkable streets makes this a pleasant and safe place to walk and cycle. Children cycle here for fun. This is provably good for neighbourliness and for public health and happiness. Cars are permitted in new Clamart. But they are second class citizens. People come first.

Next, Clamart dares to be popular. It dares to have a sense of place. The buildings are clearly Parisian, in the Haussmann tradition. Lutetian limestone, creamy and clean. Mansards reaching to the sky. Arching tiled roofs. High and long windows, as generous to those walking by as they are to those within. Rusticated pilasters reaching from ground to the eaves and marking the buildings’ corners and bays.

Greenery is woven more firmly into the urban fabric here than would historically have been normal. This is not just a return to the past. It is something better

This is the architecture of place. It says, “you are in Paris”. But it is also architecture that works at different scales, the acanthus leaves, the lovingly detailed balconies, shutters or windowsills: the rhyming roof lines, the variety in a pattern as this new bit of Paris curves around the lake.

And it’s not just the buildings and the streets and the water. Like its neighbour down the road, Plessis Robinson, and the best of new English urbanism, greenery is woven more firmly into the urban fabric here than would historically have been normal. This is not just a return to the past. It is something better.

The new tram runs on grass, greening up the city. Walkable streets are plant and tree lined. People provably like this. But it also encourages walking, visiting and cleans the local air. And, yet again, we see a sense of place in the tree selection: plane trees and lime trees. What could be more French?

One of the most consistent and frustrating mistakes made by nearly all British regeneration schemes is their reckless disregard for proper block structures with clear backs and fronts. Many are deeply naïve and unempirical in the unclear public and private spaces they create. Clamart is not perfect but its web of Parisian mansion blocks creates private gardens for residents and public gardens for visitors. The best-used green spaces are safely private or reassuringly public.

Clamart artfully mingles the new and the old, the costly and the cheap. Look at the faces of those buildings embracing the lake: large windows and balconies everywhere, far more than would be normal in historic Paris. Clamart is (quite rightly) milking the value of those lakeside views. However, they’re not doing so with the sort of saw tooth urbanism and lumpish balconies sticking out crudely from most new London mansion blocks. Clamart’s mansions blocks still feel Parisian. They are in communion with the past but not thoughtlessly aping it.

Clamart is cleverly done. Look carefully at the buildings. Much is not actual stone but reconstituted stone mixed and measured to look like lusciously white Lutetian Parisian limestone. The effects are valuable and precious. But the materials are not as expensive as they look. Which is the clever way to do it.

This is the far outer suburbs of Paris. The sleek new tram links to the metro. Residents can readily travel “in” to central Paris in a bit over 30 minutes. But they also want to travel “out” into the nearby countryside.

Many have places in underground car parks that have been built beneath the development. Disabled parking is at street level. Communal and underground bins sit elegantly at street corners avoiding the ‘death by wheelie bin’ which plagues so many British streets.

Clamart is not just about homes (though there are 2,000 of them). It’s about eating. It’s about shopping. It’s about playing

Clamart Panorama is also growing. Lines of sustainable drainage (so-termed “SuDS”) are sprouting in nearby streets. Faceless modernist lumps are being replaced by buildings which are taller, more Parisian and more finely textured. Most notably, the wide road besides is starting to grow more Parisian mansion blocks following the local code d’urbanisation. The road is evolving from an ugly urban highway into a Parisian boulevard. Good. More homes. More sense of place.

Finally, all life is here. This is town-building not housebuilding. Clamart is not just about homes (though there are 2,000 of them). It’s about eating. It’s about shopping. It’s about playing. Clamart is a rich mingling of shops, restaurants, cafés, homes, two schools, a creche, gym and playgrounds. It’s where people work.

About 25% of homes are social housing and 5% are supported ownership. The new heart of Clamart includes the town hall, the hotel de ville, complete with a Doric portico. This is about civic pride not civic carelessness.

Consider Clamart’s new town hall alongside London’s new City Hall. The comparison is pathetic. For London.

How come that a small Parisian suburb (population 57,000) you had probably never heard of until you read this essay has managed to cram more civic worth into its town hall than Europe’s largest city (population approaching nine million)? With no pride, no joy, no sense of place, how can we expect citizens to invest love and treasure in a city?

Is Clamart Panaroma working for the neighbourhood, for the town council that have made it happen or the developers who are building it? Well, the figures speak for themselves. The development’s apartments are renting and selling very quickly and based on a quick analysis appear to be achieving at least a 15 to 20% premium to local prices. This is despite the fact that they are still finishing it. The site to the south still has plots to build.

And, if you don’t believe the numbers, believe the people. I asked the nice man serving me Orangina (when in Rome…), “Is Clamart working?” “Do people like it?” This is what he said:

“This is not Paris but it is in the Haussmann Paris style. It’s really good here. You have the lake, the cafés, the bakers, the supermarket. You have everything you need. Everyone comes here. It gets really, really full, particularly in the evenings. Last night we had 200 covers. All the flats are full. People adore the architecture. I really like it.”

Too many housebuilders can’t create towns or real places. They just don’t know how to mingle uses

So, if you are a landowner or a town council or someone who just loves your part of the world, even if it is a frustrated love, do get in touch. Most architects deny the importance of beauty. Too many housebuilders can’t create towns or real places. They just don’t know how to mingle uses. However, as a society, in secret, we do know what to do. Just ask people what they like and where they want to be. And dare to listen. As they have in Clamart.

One last thing: if, like a weirdly high number of urban designers or architects, you are thinking that this would be fine without the “pastiche” of “historicist” buildings, or that what buildings look like does not matter, that you don’t need to go down the dreaded path of, whisper it, “ornament”, then have a look at the new outskirts of Amiens, around the new street of Avenue Valery Giscard d’Estaing. I visited it later the same day.

Here, the street design is excellent. Trees layer throughout. There are homes, some shops and a hotel. But the buildings are pig ugly, architecture that only a mother could love. A bit of rhythm but no texture. A bit of coherence but little complexity. The type of bland, brick-faced modernism that planning strategies call “contextual” but which most of us call “boring”.

The results are very different. Where Clamart is full of signs that say the shop or the apartment has been successfully rented or sold, here the signs are pleading for custom, not celebrating it.

Create a place that people can easily love and the people will come to live or work or to play. Don’t and they won’t. It is surprising that something so simple needs to be said. But it does.

>> Also read: Nansledan: can design codes and long-term stewardship deliver better housing?

>> Also read: New towns. Old wisdom?

Postscript

This feature was first published by Create Streets in September. Nicholas Boys Smith is founder and chairman of Create Streets

2 Readers' comments