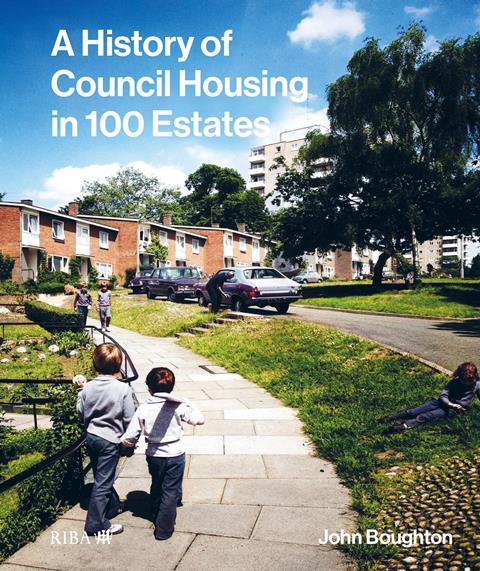

Councils played a central role in housing provision throughout most of the 20th century. Tony McIntyre reviews a new book that charts that history

This is a fascinating and important book, in many ways an extension of Boughton’s 2019 book charting the ”rise and fall of council housing”. It not only represents an uplifting story of social progress, but is also something of a lament. While there are currently some interesting estates under development, the high water mark has passed, and it’s a harsher – in spite of being a generally more affluent – world in which social housing exists.

Council housing is of course the most recent form of social housing. Boughton gives the definition as housing “built by a local authority under national legislation and supported by state finance”. In practice this means post 1890. He prefaces his discussion with a short chapter on earlier efforts, from mediaeval almshouses to the Victorian craze for “5% philanthropy”, whereby the well-off middle classes, perhaps apprehensive of a restless proletariat, were encouraged to finance the construction of dwellings for the promise of an annual return on investment.

There was a strong moral aspect to their endeavours, and in names such as The Society for the Improving the Condition of the Labouring Class. The improving was not to be simply that of physical circumstances. Octavia Hill was one of those at the forefront, and some architects such as Henry Roberts (Streatham Street housing, unfortunately not illustrated here) provided excellent and innovative designs, though the general standard was pretty bleak.

Until the beginning of the First World War, councils tended to repeat the exemplars of their philanthropic predecessors

Subsequent chapters cover the years from 1890 onward. The 100 estates, each given an illustrated two-page spread, highlight the chapter introductions, which are excellent accounts of the political, social and legislative changes that sponsored and enabled the development of council housing.

Until the beginning of the First World War, councils tended to repeat the exemplars of their philanthropic predecessors, using tenement block and balcony access typologies. But this also included the two storey cottage format, that had been promulgated at places such as Bournville and Port Sunlight.

Until the advent of the high rise block in the 60s, these three remained the staple forms of council housing. The exception came after the war, when Homes for Heroes became the watchword, and early forms of prefabrication were trialled.

What all efforts at housing “the poor” could not deal with was that the poor had no money. It was hoped that housing better off working families would free up housing stock for their poorer neighbours – the famous but elusive ‘trickle down’ effect.

The 1930s saw the end of this hopeful dream, when councils began large programmes of slum clearance, with massive schemes at White City, London, St Andrew’s Gardens, Liverpool and Quarry Hill, Leeds, among others. At the same time, space and technical standards were improving, but as ever, money was a controlling factor.

Post Second World War, with a Labour government in power, a significant change was made in the way in which councils could apportion the housing they built. It had been seen that the monoculture nature of many estates somtimes led to poor maintenance and a drift towards such accommodation being seen as undesirable. Legislation was passed that encouraged councils to generate mixed communities, by removing their obligation to house purely working class families.

Prefabrication was again seen as an answer to advanced building techniques and rapid deployment – why not turn the productive capacity of war to the needs of domestic wellbeing? Bungalows at Inverness Road, Ipswich employing steel truss roofs and concrete panels, are still in use today, as are those in the Bilborough Estate, Nottingham. Some interesting experiments were made, but the urgency of war failed to translate to peacetime.

However the period from 1940 to 1955 was something of a high point of estate design, a fact reflected in Boughton giving it by far the largest section of this book. Examples illustrated include the two-storey Creggan Estate, Londonderrry, the Gaer Estate, South Wales – modernist with warmth – and the Lansbury Estate in Tower Hamlets.

This latter, London County Council (LCC), scheme faced the problem of inner-city density with the inclusion of several six-storey blocks in what was to be called the New Humanist style, based on contemporary Scandinavian design. Schools, community buildings and churches were supplemented by the country’s first pedestrianised shopping area.

The apogee of this approach was Powell and Moya’s competition winning Churchill Gardens, for what was then the Conservative-led Westminster Borough Council. The quality of design and generous space standards reportedly led some residents in the private Dolphin Square flats opposite to envy the superior accommodation enjoyed by the council’s tenants.

For the late 1950s and 1960s perhaps no development captures the architectural debate within the LCC and beyond like the Roehampton Estate in southwest London. With some 700 homes, Alton East is a mix of low rise and ten-storey blocks, set within the mature grounds of former Victorian villas. The aesthetic continues the New Humanist tradition.

The other half of the development, Alton West, took its cue from Corbusier’s Unité at Marseille, intelligently executed Brutalist slab blocks accommodating nearly 2,000 dwellings. Park Hill in Sheffield, recently and controversially revamped and privatised, was another extraordinary achievement, with its “streets in the sky” balcony access.

But by the mid 1970s the tide of political opinion was turning against public housing. From 1980 the Conservative government’s twin policies of capping local government borrowing, and allowing sitting tenants the right to buy their homes, marked the end of a century of deeply committed council housing.

By the late 1990s, 1.7 million council homes had been lost to the right to buy scheme. Nearly half of that number have eventually ended up in the hands of private landlords. Belatedly this right to buy legislation was repealed in Scotland and Wales.

There is no doubt that, as Churchill once said: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us”

The political and legislative frameworks are changing. Since 2018 councils in England have been allowed once again to build council housing, though financial restrictions mean this is largely done in conjunction with private developers.

The results, as with Matthew Lloyd’s Bourne Estate in Holborn, are sometimes outstanding, but elsewhere have produced mixed results. The model of houses and flats to be sold on the open market being used to subsidise those for council tenants may sound like the ideal of a mixed community, but can lead to segregated rather than integrated developments.

A Marxist view would see the buildings presented in Boughton’s book as being simple manifestations of a prevalent political environment, and any discussion of their aesthetic merits a mere indulgence, a distraction from the fundamental problems of a capitalist society. While there is much to be said for that view, there is another half to the argument. There is no doubt that, as Churchill once said: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

Also read >> The UK’s top 10 council estates

Postscript

A History of Council Housing in 100 Estates by John Boughton is published by RIBA Publishing

No comments yet