Architects have a critical role to play in showing how we can make better use of our low density suburbs, writes Jerry Tate

I recently had an opportunity to reflect on London’s suburbia, which gave me pause for thought in some of the work we are developing in our office at the moment. Asked to do a ‘talking head’ slot on a Grand Designs suburban special, I resorted to extensive research (so as to appear fantastically knowledgeable) and happened upon the most amazing book by Robert Stern called Paradise Planned.

This has to be the most thorough survey of the suburban housing model to date. It charts the changes from the reaction against industrialisation by Ebenezer Howard or Parker and Unwin, right through to modern day New Urbanism in the USA. What particularly struck me was the constant theme of reconnecting with nature, either as a utopian dream from Howard, or an overt marketing strategy to help with house sales.

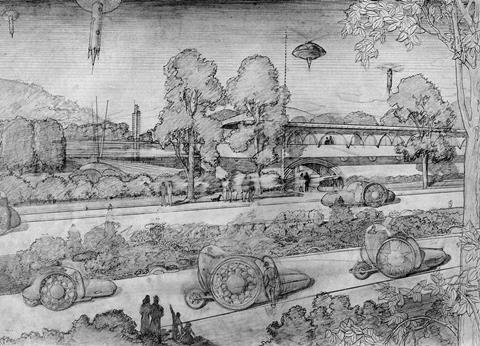

So what is wrong with this? Put simply, as suburbia becomes less dense, with more landscape between buildings, the car becomes more prevalent. The final conclusion is the crazy Frank Lloyd Wright ‘Broadacre’ concept, which relies on every occupant having their own helicopter. The irony of these half-idealistic, half-apocalyptic 20th-century suburban schemes was always that even as they sought to bring people closer to clean air and nature, they destroyed the environment and actually became less sustainable.

Today we face a growing need for more homes, often from people who (quite rightly) want their own garden and ‘piece’ of nature. If we assume, as a given, the need to provide more housing in the UK, then one logical solution to achieve this is an enormous landtake and an end to our green belt. For many of us, this no longer feels like a sustainable option.

So what is the answer? Well in short, densification.

We need to try to fit more homes closer together, whilst keeping the suburban spirit and ethos of a better connection to the landscape intact. The great news for architects is that this macro problem about our cities’ futures, actually boils down to a local design problem - how do we keep a connection to nature with a denser network of homes?

If we do not address the densification problem then we cannot expect to be able to protect the green belts around our cities. There are however two problems with progressing this issue.

As a profession we should grasp this opportunity to show how clever design can make the most of our existing cities

Firstly the current public transport accessibility level (PTAL) ratings for many potential ‘densification’ sites are not very good. This would imply that a more concentrated development is not appropriate. However, the truth is that without new denser schemes being completed, public transport will not improve sufficiently to affect the PTAL rating. Densification makes public transport networks more economically viable.

The second and more critical problem is resistance to increased densification from the current suburban residents. We recently completed an eight unit residential development in a classic suburban area. During the planning process we spent a long time refining the design to ensure that our massing and landscaping were sensitive to the local environment, and holding local consultation events, yet the reaction from a large number of neighbours remained aggressively negative.

Most people who have moved to the suburbs are looking for more space – specifically more personal green space. And they view anything that may affect this way of life as a threat. Until a number of ‘densification’ schemes have been successfully implemented it will be a struggle to allay those concerns. It is therefore vital that the first of these new suburban densification schemes are of excellent design quality, to demonstrate what can be achieved.

So the densification of our suburbs represents a fantastic design opportunity for architects – a chance to address one of the most pressing problems in our built environment with excellent architectural and landscape design. As a profession we should grasp this opportunity to show how clever design can make the most of our existing cities, and thereby avert endless suburban sprawl across the open countryside.

Also read >> Why do we struggle to densify suburbia?

Postscript

Jerry Tate is director of Tate+Co Architects

3 Readers' comments