If ghosts aren’t real, then why are some building types more prone to hauntings than others, wonders Eleanor Jolliffe lightheartedly

It’s now October – the weather and the news are sending shivers down all our spines. This time of year, however, brings other chills, uninfluenced by whether or not you are brave enough to ignore the high fuel prices and turn the heating on.

All of us, as children, have felt a tingle down the spine when telling ghost stories at sleepovers or camping. I was convinced for years that the fireplace in the room where I sometimes slept while at my grandmother’s house was haunted; convinced I could feel cold draughts creeping across the room and see shadows leap in its deep brick depths. I could tell you now, of course, that draughts are how open fires work, but aged nine there was nothing so thrilling for me as being cosy in bed convinced there was a ghost in the room and feeling the eyes of the rabbit-hunter in the print on the wall watching me.

The New York Supreme Court has gone one step further in credulity, though, and decreed Helen Ackley’s home to be legally haunted. Ackley claimed she often heard phantom footsteps and doors slamming in her home. The poltergeists would leave gifts of coins and rings for her grandchildren which would later disappear, and would shake her daughter’s bed to wake her in the mornings. A paranormal researcher and a medium claimed the poltergeists were the ghosts of a married couple from the 18th century and a navy lieutenant in the revolutionary war. The court, however, simply ruled that for the purposes of an action for rescission bought by a subsequent purchaser the house was legally haunted. The ghosts apparently packed their bags and left with the Ackleys, though – apparently they were unimpressed by the new purchasers as no more hauntings were recorded after Helen and her family left.

Britain has the second-highest reporting of paranormal geography in the world (second to the US) and much of it revolves around our oldest buildings – the ghost of a headless Anne Boleyn who haunts Blickling Hall in Norfolk, skeletons chained together in Dunster Castle, and locations in Edinburgh such as Mary King’s Close where plague victims were sealed up to die while they were still alive. There is something about a building that seems to act as an anchoring point for ghosts – or for human superstition and disquiet; call it what you will.

Psychologists report that environmental factors such as draughts positively correlate with reports of hauntings. It may be, then, that Passivhauses, by eliminating draughts, have also eliminated ghosts

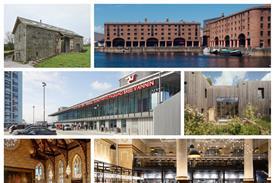

A book I read long ago, Architectural Voices, Listening to Old Buildings, posits the theory that a house may be more than its physical materials; that the creepy feeling we get in some houses, or the numinosity and awe we feel in some churches, may be more than just our mind playing tricks on us. Can buildings absorb the emotions and events that happen within them? The authors suggest that some buildings seem more sensitive than others, perhaps due to the porosity and physical characteristics of the materials – brick and limestone being more absorbent than steel or glass, for instance.

The former homes of serial killers are often demolished – perhaps to deter morbid souvenir hunters, perhaps to eradicate the evil embedded in the place, perhaps both. Estate agents report that houses in churchyards, homes with reported deaths in them, or converted churches are hard to sell. Think of it what you will, but would you live in the house where Fred and Rose West buried nine women?

Psychologists who have studied this report that environmental factors such as draughts positively correlate with reports of hauntings – perhaps a reason that older, more porous buildings with more air leaks and naturally plastic materials register more alleged ghosts than modern skyscrapers. It may be, then, that Passivhauses, by eliminating draughts, have also eliminated ghosts. Or perhaps none of these places have had enough time to absorb enough humanity to be “haunted” yet.

I don’t believe in ghosts; but if I’m honest I don’t entirely not believe in them either. There’s something about the uncanny, the feeling you can’t otherwise explain, the sense of walking with those who came before us that is fascinating, and not just to me. Who’s to say our buildings may not absorb some of this? I suspect the “ghosts” of Britain will continue to wander for centuries to come.

No comments yet