Department officials resist MP’s attempts to get numbers of unsurveyed schools in testy committee hearing

Dangerous RAAC in UK schools may have been missed because government surveys favoured visual inspections over more intrusive methods.

The Department for Education (DfE) closed hundreds of schools in August a day before the start of term after three structural failures at properties that had initially been considered safe.

Officials from the department told the Public Accounts Committee that initial surveys of the problem concrete, which it had been carrying out since September 2022, were “primarily visual”.

The DfE’s permanent secretary Susan Acland-Hood explained to the committee that intrusive surveys, which may have involved closing off sections of schools for periods, would have “massively extended the length of time it would have taken to identify RAAC across the whole school estate”.

The comments appear to confirm the comments of Chris Gorse, a RAAC expert at Loughborough University, who said that initial surveys of schools were unlikely to have involved checking the integrity of bearings – which he believes is the primary cause of RAAC failure – as this would require intrusive investigations.

Why RAAC fails

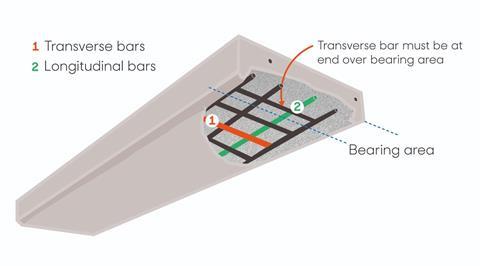

The most critical problems centre on the area supported by the wall at each end of RAAC planks. RAAC reinforcement consists of steel bars extending the length of the planks that are locked in place by a series of perpendicular, transverse bars.

Variable manufacturing quality meant the transverse reinforcement bars crucial for a roof’s structural integrity were sometimes positioned away from the bearing area at the ends of the planks, leaving the inherently weak aerated concrete to take all the loads.

Poor quality construction is a related issue where there is insufficient overlaps between the RAAC plank and wall to ensure a transverse bar is located over this bearing area. Gorse says these two issues are the main source of failure.

Failure of structurally compromised planks can be triggered by secondary issues including cutting through the reinforcement for maintenance reasons, extreme temperatures and overloading of the planks.

>> Read the full interview with Loughborough University’s Chris Gorse

Last week in parliament, secretary of state Gillian Keegan revealed that the decision to close schools had come on the back of three cases of RAAC failure.

Jane Cunliffe, chief operating officer for the DfE’s operations and infrastructure group, told the committee that in the first two of these cases the ceiling panels were “caught on a beam so that engineers were able to see what the beam looked like pre-full collapse”.

She said that in both cases engineers were concerned that the affected panel would have been judged as non-critical on by the visual inspections that the DfE had been carrying out across the school estate.

Asked whether schools which had received these visual-only inspections would need to be surveyed again, Acland-Hood explained that they would not.

This is because the department had moved from grading the status of the RAAC as ‘critical’ or ‘non-critical’ to a position wherein “if RAAC is present it should be remediated”.

She clarified that the only schools that would need to be re-inspected were those for which there were access issues in initial surveys – for instance due to the presence of asbestos.

“Some of those have taken place last week, some are taking place this week as well as the new surveys,” added Cunliffe.

“We’re prioritising those return visits to the ones we suspect will have RAAC because of the characteristics of the first survey. So, our technical team are going through those and allocating those to surveyors”.

Last Wednesday, after significant public pressure, the DfE published a list of 147 schools that were confirmed to contain RAAC.

Prior to that, the number of schools with RAAC had been put at 156 – but further surveys at nine schools identified that the problem concrete was not in fact present.

Of the remaining 147, 104 are continuing full face-to-face learning – either at their own site or elsewhere – 20 are operating partly face-to-face and partly remote, four are fully remote, and 19 have been forced to delay the start of their terms.

There was a testy atmosphere in the hearing, with MPs frustrated at department officials’ inability to provide requested figures.

A lengthy exchange over exactly how many temporary classrooms had been supplied did not yield an answer, nor did repeated questions about how many schools were still waiting to be surveyed.

Asked by Hillier whether the number was in the tens or hundreds, Cunliffe would only say that the department was doing “tens of surveys every day”.

More on the RAAC crisis

>> Lasdun’s Ziggurats closed over failing concrete fears

>> National Theatre carrying out surveys after discovering RAAC in backstage areas

>> Government expands RAAC surveys of court buildings after Harrow closure

>> Our crumbling schools are just one more symptom of this government’s failure to plan for the future

>> RIBA calls on government to set up industry task force to coordinate RAAC response

>> RAAC schools had been due for renewal under scrapped Labour plan

>> Schools told to close all buildings containing problem RAAC concrete

>> Government spending less than half the money it says is needed to keep schools safe

>> Government orders all departments to investigate lightweight concrete risks

>> Unions demand action from the government on school collapse “emergency”

The officials did reveal that 98% of schools had now responded to the department’s original RAAC questionnaire, leaving roughly 300 yet to be returned.

“We have enough surveying capacity now so that when we have a school that comes through with a suspected RAAC we can make sure that gets that gets surveyed within a number of weeks,” said Cunliffe.

The hearing also saw Acland-Hood give assurances to the committee that schools already named on the school rebuilding programme would not be affected by the RAAC crisis.

The government has committed to redevelop 500 schools by the end of the decade and 400 have so far been named.

“We will not be taking named schools out of the school rebuilding programme,” said Acland-Hood, who added that the government would be “prioritising RAAC schools for the remaining 100 slots in the programme”.

No comments yet