Number of schools to identify problem concrete rises to 174

Invisible deterioration at the bearing ends of RAAC planks resulted in the August school ceiling collapse which led the Department for Education (DfE) to suddenly change safety guidance, officials have revealed.

The decision, taken days before the start of the academic year, disrupted learning for thousands of students, with more than 100 schools previously considered safe being reclassified.

Last week, the department’s permanent secretary told the Public Accounts Committee its initial surveys of the problem concrete had been “primarily visual”, an approach which, according to Loughborough University RAAC expert Chris Gorse in an exclusive interview with Building Design’s sister title Building could have resulted in structural problems at the bearing ends of the planks being missed.

Appearing again in the House of Commons on Tuesday morning – this time in front of the education committee – Susan Acland-Hood confirmed that three RAAC failures recorded over the past year, including the climactic incident in August, had been due to bearing end flaws.

“In these cases, the reason that there had been a failing that was not visible, was that there were failings at the bearing ends,” she told the committee.

“That is very difficult to see from underneath. So, there is other types of deterioration in RAAC that you can see much more readily, such as bowing, evidence of damp and cracking.

“This was specifically at the bearing ends and in order to be very secure of a judgement of non-criticality you would have to be drilling into many, many, many concrete planks across the school estate.”

At the prior committee hearing, Acland-Hood had explained that this option was not pursued because it would have been as costly as full mitigation.

Why RAAC fails

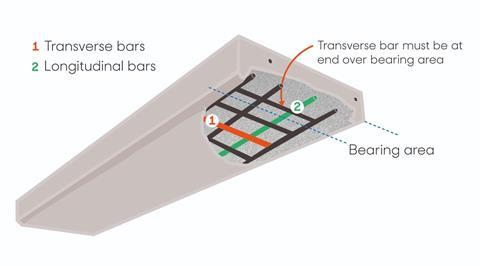

Variable manufacturing quality meant the transverse reinforcement bars crucial for a roof’s structural integrity were sometimes positioned away from the bearing area at the ends of the planks, leaving the inherently weak aerated concrete to take all the loads.

Poor quality construction is a related issue where there is insufficient overlaps between the RAAC plank and wall to ensure a transverse bar is located over this bearing area. Gorse says these two issues are the main source of failure.

Failure of structurally compromised planks can be triggered by secondary issues including cutting through the reinforcement for maintenance reasons, extreme temperatures and overloading of the planks.

>> Read the full interview with Loughborough University’s Chris Gorse

The most recent failure occurred on 24 August when workmen were drilling into the RAAC plank to put in light fittings, which triggered the collapse of large pieces of the deteriorated concrete.

Tuesday’s committee also heard evidence from Baroness Barran, minister for the school system and student finance, who updated MPs on the department’s progress on fixing the crisis.

She revealed that the number of schools with confirmed RAAC had increased by 27 cases since data was first published at the beginning of the month, with 174 cases now confirmed.

The number of settings where children are in face-to-face learning has gone up by 23, such that 85% of affected schools are offering face-to-face arrangements.

There are now 23 schools where pupils are in hybrid arrangements – up from 20 – while just one school is currently fully remote.

Of the 52 cases originally classified as critical and already mitigated, Barran said the average learning loss was six days. More than 98.5% of schools have now returned their RAAC questionnaires to the DfE.

Barran also used the hearing to explain the nature of mitigation methods, adding that propping was used in “a tiny minority of cases”.

> Also read: The unfolding RAAC crisis highlights the need for a new vision for schools

“More typical is where you put in effectively a timber ceiling underneath it, you put back the ceiling tiles,” she said.

“You wouldn’t know it was there and if anything happened it would come down on the timber and be completely safe.

“To all intents and purposes, it looks like a completely normal ceiling – that is the more common approach.”

She explained that, depending on the size and complexity of the case, there would be about six weeks between design and installation of these ceilings.

In the meantime, many schools will have to make do with temporary measures. Acland-Hood also revealed that, as of Friday last week, there had been 180 orders for temporary single classrooms and 68 for double classrooms from 29 schools.

The “semi-permanent” timber solution will last for roughly 10 years, according to Barran, with Acland-Hood explaining that this was “a long enough life that we can make sure we’ve got exactly the right long-term solution in place”.

“It takes the clock off but it doesn’t mean we won’t want to do a permanent fix,” she said.

Education secretary Gillian Keegan appeared in the Commons chamber later on Tuesday, rejecting accusations from her opposite number, Labour’s Bridget Phillipson, that she had waited too long after receiving evidence of the August collapses before issuing new guidance.

No comments yet