Architects share Building Beautiful Commission’s concerns over innovation ‘loophole’

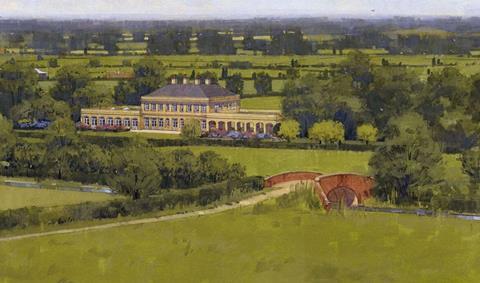

Architects have backed the Beauty Commission’s call for the so-called “country house clause” to be rewritten.

The commission’s report called for the word “innovative” to be removed from Paragraph 79 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which allows an isolated house to be built in open countryside in exceptional circumstances.

The wording currently says planning permission may be given where design is “truly outstanding or innovative”.

The BBBBC report, Living with Beauty, warned: “This opens a loophole for designs that are not outstanding but that are in some way innovative in these precious sites. The words ‘or innovative’ should be removed. In cases like these, we should always insist on outstanding quality.”

The recommendation, one more than 100 from the commission which was co-chaired by late academic Roger Scruton and Create Streets director Nicholas Boys Smith, appears in a section entitled “Ask for beauty”.

Architects with a track record of delivering homes under the country house clause – which used to be known as Paragraph 55 before the NPPF’s 2018 revision – told Building Design they believed the “innovative” route had been gamed by architects and developers in the past.

They offered different ideas on the potential to reword the clause.

Charles Holland, who in 2018 won planning at appeal for a Paragraph 79 house in the Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, said the “innovative” route was just one of the many debatable issues that the clause created.

“People add tech gizmos to tick boxes,” he said. “I don’t think it necessarily leads to good or more sustainable architecture.

“I’ve got particular concerns about ‘innovation’ in that it tends to relate to certain types of intervention, but not how architecture moves forward.

“It would be interesting to have a wider definition of what ‘innovative’ means. Is it how domestic space is organised? Is it about the architectural response to the site?

“I’m more interested in the potential for Paragraph 79 architecture to raise standards in rural areas.

“When the NPPF talks about exceptionality, it is by definition setting a very high bar and changing one word is unlikely to make very much difference.”

Classicist Robert Adam said he believed that the change proposed by the beauty commission would be a positive move for the NPPF because the current wording of Paragraph 79 suggested that proposals were not required to be outstanding and innovative.

“It implies that one or the other would do and it doesn’t mean you’ve got to do both,” he said. “On the whole, it’s probably better to remove it.

“Innovation is very often used as a stand-alone. If you can say ‘we’re being very innovative’ people can conflate that with high quality.

“It takes away a piece of confusion. Just because something is innovative doesn’t make it high quality.”

Studio Bark’s Wilf Meynell, a founding director of the Paragraph 79 homes specialist and AYA Sustainability Architect of the Year 2018, agreed there was an argument for refining the definition of acceptable design credentials for the developments.

However he said that simply removing the word “innovative” as an alternative to “outstanding” did not go far enough.

“It’s true that being able to describe a building as innovative has allowed some huge, gas-guzzling and generally questionable schemes to get permission,” he said.

“We think that, given the national climate emergency declared by the government last year, the clause should be reworded to embed a commitment to being ‘environmentally outstanding’ or ‘environmentally innovative’, particularly as these homes are likely to have car-reliant occupants.

“Ultimately, if it’s doing something that is truly environmentally innovative, does it really matter what it looks like?”

Recent research put together by Studio Bark found close to 200 planning applications had been submitted to English local authorities seeking to use elements of Paragraph 79 since the 2018 revision. It said 120 of them had been approved,14 at appeal.

Of 60 known refusals at the time the report was put together, more than half had been unsuccessfully appealed. Studio Bark has also published more detailed research on the use of Paragraph 79 and its predecessor clause, put together by part II student David Symons.

Innovation or outstanding design are just two potential qualification criteria for overcoming the NPPF’s presumption against the development of “isolated homes in the countryside”.

Other arguments include the need for new housing for rural workers; proposals that represent “optimal viable use of a heritage asset” or the reuse of redundant buildings. Proposals that involve subdividing an existing home can also make use of Paragraph 79.

10 Readers' comments