Stephen Molloy is entertained and impressed by the tender beauty of new RIBA publication Queer Spaces but is troubled by the lack of a clear definition of what they are. Co-author and editor Adam Nathaniel Furman explains why the book resists being pinned down

What is a queer space? The old English term “queer” is thought to come from the German “quer”, meaning oblique or diagonal, which enticingly hints that the idea of what we now call queerness has its roots in spatial concepts.

Same-sex desire does not have the side-to-side nature of friendship or the opposite nature of heterosexual attraction. Desire between men or among women has a diagonal orientation.

Thinking about desire in space, about how people might be opposite, alongside or diagonal to others, is at least unconsciously part of every serious architect’s work. I can remember, early on in my career, a meeting with a hotel client. He was concerned with achieving the best spatial relationships in the hotel bar for the purposes of encouraging escorts to feel comfortable about working the space.

Personally, as an architect and designer, I would have preferred a more systematically compiled book

I was talking to a developer about furtive glances, safe spaces and forbidden desires. The bar had become a subtle, subversive and delicious challenge within what was otherwise a banal, wipe-clean, normative project. For me, that meeting suddenly felt a little queer.

Is the cocktail bar of a mid-price business hotel a queer space? Probably not, but I had hoped that architect-designer Adam Nathaniel Furman and architectural historian Joshua Mardell’s new book Queer Spaces might help me to answer the question.

I was surprised however that this anthology of gay, lesbian and trans interactions with buildings and places staunchly refuses to define the term.

The contents of the book can be divided into three main categories:

- A quirky potted history of rich queers using inherited money to build strange little buildings in isolated areas of natural beauty. This section could be titled “The weird kitsch of rich men’s queer children”. It is a compelling argument for 100% inheritance tax.

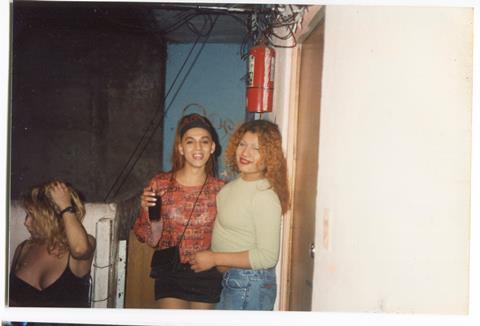

- Accounts of nightclubs and community centres, some of which sound rather fun. This section could also be titled “Where to go clubbing in Bogota in 2004”. It would be a useful tourist guide to those with access to time travel and teleportation devices.

- Architectural accounts that make a serious attempt to understand what might actually be queer about a space, beyond anecdotal accounts of what may or may not have happened there.

Personally, as an architect and designer, I would have preferred a more systematically compiled book that was limited to these latter entries. I was a little unsatisfied with the loose editing style that seems to take all-comers and has no explicit taxonomy of what is and is not a queer space.

I spoke to the book’s co-author and editor, Adam Nathaniel Furman, to get some answers. He is a contemporary and a colleague that I have never met in person, but whom I have long admired from afar.

Queers pop up everywhere, a strange mushroom-like phenomenon, born in all social classes, that find their way to the light

His work plays with classical and futuristic references and he has developed a unique and distinctive colour palette that is a welcome break from the muted earth tones and millennial pastels that dominate my Instagram feed.

His designs are iconic, coherent, smart, instantly recognisable and tightly curated. I was therefore doubly surprised at the slack, roomy way in which the book is edited.

I asked Adam about the very personal and subjective nature of the book, and why he chose this approach.

Stephen Molloy What is queer aesthetics?

Adam Nathaniel Furman There aren’t any – they are contingent on place and time and group identities. Queer aesthetics are always in relation to mainstream taste cultures.

They are symbiotic, parasitic, antagonistic, manifested through exaggeration, mixing and ironic questioning. That relationship with the centre is always there. Queers pop up everywhere, a strange mushroom-like phenomenon, born in all social classes, that find their way to the light.

SM Is queer an identity or a behaviour pattern? Tribal identity or behavioural circumstance?

ANF I was born into so many gaps in multiple Venn diagrams. I am eminently comfortable in the gaseous, nebulous identity between worlds. It was really important for us not to define queer in the book…

SM A few of the entries take the time to define queer – I spotted three definitions – all are robust and serviceable, but different from each other. It gives the book a roominess that can maybe even sometimes feel uncomfortably draughty.

ANF There is plenty of writing about what a queer space is. I could have done that. It was a very deliberate decision not to lay claim to categories, not to make them very intellectually fixed. That’s death as far as I’m concerned.

It’s the capaciousness, which you see as draughtiness, that I am drawn to. That sort of openness is present in my work and most of the things that I am drawn to. The Linnean desire for taxonomy and category can be very strong: “What ism is that – is it Art Deco, is it modernism? – I wanted to avoid that.

SM I’m wondering if refusing to define and categorise is a sort of subtle power play that prevents people from reading this world from the outside. When all the categories are hidden, it can often exclude people.

Let’s use a parallel: in England, accent and class offer clear signposts to social hierarchy. In Germany, which has a more discreet class culture, these boundaries are less clearly signposted. An advantage of the English way is that at least you know where you stand most of the time.

ANF I have been trapped in that my whole life, and I don’t find it easy to navigate! If I can extrapolate from what you say, in relation to the book, perhaps you are saying that removing the clear categories is removing agency from the readers.

SM It makes the world of the book a little impenetrable to outsiders. It’s harder for people like my mum reading the book not knowing which end is up, or maybe somebody who doesn’t know if they are queer or not, and not sure if this is a world they can click into. It’s a good thing, but it comes with a trade-off.

ANF It’s fair to say that I do have an absolute visceral terror of taxonomy. We were hoping for that transparency to be at the level of the individual texts. I’ve come across a lot of writing that is breaking down, clarifying, describing exactly what gender and space is. It tends to be very laden with academic prose - if I may say, jargon.

We worked quite hard to make all the texts as legible, succinct but not dumbed down as we could. There is no shortage of people in architectural writing who want to pin things down. I see this book as being an archaeology of easily accessible queer stories which can be used as source material to build upon. That would not be the case if me and Josh had set out our five types of queer space or whatever.

I came away from my conversation with Furman deeply impressed by the careful and sensitive approach that he has taken to the book. By understanding it as a sort of compost of source material from which other roses may later grow, I became a lot more understanding of the loose nature of the editing and the hidden taxonomies.

For the record, over the course of our long conversation, it became clear that my corporate hotel bar would never have made it into the book, due to the lack of actual same-sex desire, even if I personally got a queer vibe off the design process.

Furman’s definition of queer, on further examination, seems to exclude the categories of the effeminate heterosexual male, or log cabin Republican, two aesthetics that I personally feel might have been worth a closer look.

On balance I can say that I have been entertained and enriched by this tender, beautiful and sometimes flawed book. I would recommend it to anybody with an interest in non-traditional sex and gender roles, but it is not the must-read manual for thinking about spatialised queer desire that I had perhaps been yearning for.

Postscript

Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQIA+ Places and Stories is published by RIBA Publishing

Stephen Molloy is an architect and co-founder of Fundamental, a Berlin-based design and retail collaborative

No comments yet