A new book on the respected architectural practice highlights work that straddles tradition and innovation, writes Richard Griffiths

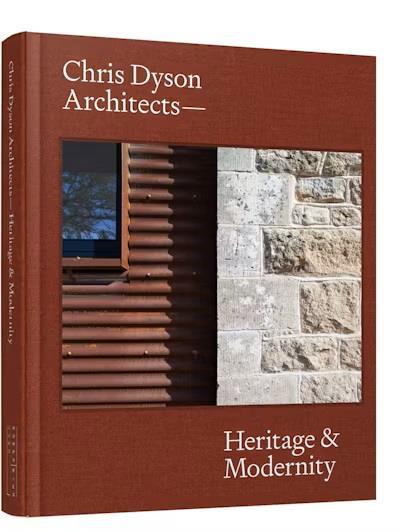

Chris Dyson is one of that happy band of architects designing at the interface between old and new. The book cover of his new book says it all, the title - Heritage & Modernity - and the photos – details of rusted corrugated CorTen steel cladding juxtaposed with traditional stone walling of rubble stone and ashlar quoins. It is a fine record of the work and approach of one of the most interesting architects of our time, beautifully designed and produced: go out and buy it now!

Chris Dyson is clearly a man for our time, with his renewed interest in working with the fabric of existing buildings and their setting rather than in demolishing and building anew. This is too often expressed these days as a waste of embodied carbon, but that surely misses the point; working with old and new, in what in this country is always a historic context, gives the opportunity for meeting new social, environmental and economic needs in a manner that achieves the Vitruvian triad of commiditas, firmitas and venustas; and now abideth Function, Construction and Beauty, these three; but the greatest of these is Beauty.

Chris Dyson is prepared to acknowledge this deeply unfashionable truth, so often dismissed because ‘beauty lies in the eye of the beholder’. However, if it does not lie in the mind of great architects, with their total immersion in the aesthetic consequences of design, where does it lie? The noble interiors of the Spitalfields houses and the form and texture of the CorTen steel that clads the Gasworks bear eloquent witness to Chris’ aesthetic sensitivity.

Chris worked with James Stirling in his formative years – as did Julian Harrap, my own master, at an earlier date – and his aesthetic interest in form and light comes from there, as does an interest in the historic setting and resonance (influenced by the presence of Leon Krier in the office). However, the qualities of material, texture, age and sustainability, so beloved by the architects of the SPAB, derive from his experience of his houses in Spitalfileds and Suffolk.

He can therefore combine being resolutely modernist – in the Gasworks for example – with a refined understanding and appreciation of what Summerson called the Classical Language of Architecture in the beautifully restored Spitalfields houses on which he has worked. Of course, his experience at Stirling’s means that his predilection is more towards Le Corbusier’s definition of Architecture – the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light – than that of William Morris and the SPAB – ‘they are not ours to touch’.

An appreciation of the texture of age, and the as-found, distressed panelled interior of the Chanarin residence in Princelet Street, Spitalfields, stands out as a rare exception to the beautifully repaired and redecorated interiors elsewhere. Yet the new work exhibits a delicate sensitivity to the beauty of materials – the cedar shingles cladding the Crystal Palace Park Café, inspired by the scales of the listed dinosaurs that are found nearby, and the rusty corrugated CorTen steel at the Gasworks.

Chris is perhaps most in his element in the cunningly crafted rooftop extensions to various buildings in Spitalfileds, of which that to the building in Tenter Ground will be the most exciting – glazed timber-frame pavilions of a Miesian character. However, he also professes a great admiration for the work of Louis Kahn, the great master of form and material, and of Michael Hopkins. The latter being an architect with impeccable modernist credentials who moved farthest towards an architecture using traditional materials, including brick, lead and joinery, as at the Glyndebourne Opera House or the sophisticated timber-framed insertion of the café inside the ruined monastic refectory at Norwich Cathedral.

Chris has a similar susceptibility to detailing, in the beautifully considered steel staircases at his Princelet Street Gallery, or the immaculate brickwork of the Wapping Pierhead, a dark brick, round-ended extension to a terrace by Daniel Alexander in the London Dock. Here the elevations are modelled with window openings, brick arches and recessed aprons that evoke Georgian precedent in a wholly innovative manner. There is a subtle widening caused by the splay of the tall arched brick lintels, and a play of two planes of brickwork, the forward plane of the outside wall and the recessed plane of the windows, apron panels and Soanian shadow gap below the coping; a masterly composition.

The last words belong to Chris Dyson: ‘We seek to vitalise contemporary architecture with a rich, inclusive architectural language, which fuses the modern movement’s ideals of functionality, clarity, integrity, and economy with the traditional architectural qualities of form, space and thereby conveys a sense of architectural continuity. We are also striving for a synthesis between the monumental tradition of public buildings with the more informal and accessible image of culture today. Above all, we hope to maintain the connection between suitability for purpose and beauty’.

Postscript

Chris Dyson Architects: Heritage & Modernity is published by Lund Humphries.

Richard Griffiths is the founder of Richard Griffiths Architects.

1 Readers' comment