The challenges of a rapidly urbanising Mongolia are dissected and addressed in a new book, reviewed by Katharine Heron

The author Joshua Bolchover credits his parents with his understanding that architecture is a social project, and his engagement in Ulaanbaatar is exactly that. Bolchover is an architect and Professor at The University of Hong Kong, where he leads a research group with design and research practices which argues for building as research. He co-established the Rural Urban Framework with John Lin in 2015.

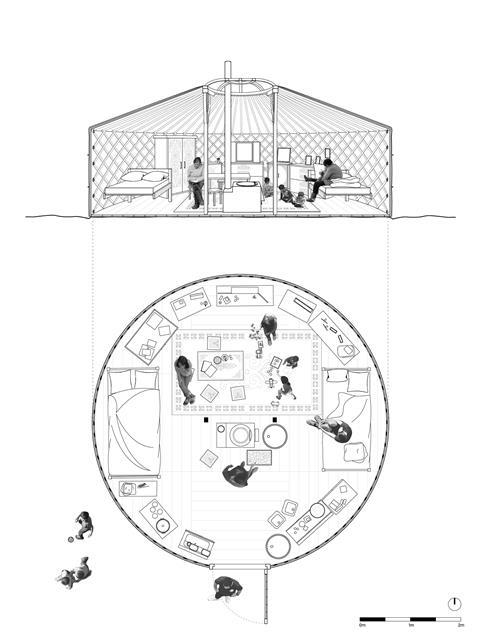

Bolchover writes: “For thousands of years, Mongolians have lived in gers - circular structures of timber and wool wrapped in stretch white canvas and pulled taught with horsehair rope. The ger is a highly evolved design object, easy to disassemble in a matter of hours without any tools or fixings. The perfect dwelling for nomads who move up to 500 kilometres each year in search of seasonal pastures.”

The book is organised to provide first historical rural context, describing how the collapse of the traditional rural nomadic life and migration to the city has caused its unplanned continuous expansion, and secondly a methodology for alternative solutions. There is thorough and fascinating analysis of the nomadic life of the herders from early times, including the rapid change in the twentieth century with its seismic shifts.

In the first territorial divisions in 1206 by Chinggis Khan, settlements emerged at trading posts with the Silk Road. The re-adoption of Buddhism from the sixteenth century then led to the creation of monasteries and lamaseries. These were often control points along the nomadic herder routes and centres of wealth. At its greatest extent the Mongol Empire covered a vast swathe of Eurasia, including much of modern day China. Throughout these centuries, nomads would encamp in groups, and are believed to have followed largely unchanging migration routes and behaviour.

By 1691 however, Mongolia had submitted to Chinese rule. The collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 was followed by a brief period of Mongolian independence, but the formation of the Russian Soviet Republic in 1917 saw Mongolia soon enter Moscow’s sphere of influence. The Mongolian People’s Republic was established as a communist state in 1924, closely aligned with Soviet policy.

Seven hundred monasteries were destroyed and 43,000 lamas executed in the Stalin period. Efforts to collectivise the herders in the early 1930s led to significant loss of livestock, and were resisted by the herders. Collectivisation was attempted again from the mid 1950s, under the modified and more successful ‘negdel’ system.

The patterns of herding continued with seasonal migration and was self-regulating within the soviet structure. About one third of Mongolian GDP was provided by the USSR, and the steppe became a highly articulated operational landscape.

The gradual loosening of Soviet control during the 1980s culminated in the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The Soviet subsidy disappeared from Mongolia, resulting in real wages falling by 50% in just two years, poverty escalating from 0 to 27%, and soaring inflation. The number of herders reduced to one third of their previous number by 2001, and the structured system of herding in collective groups was lost.

A land law gave every Mongolian citizen the right to claim and own a plot of land. But the privatisation of the herds, dissolution of the collectives, and harsh winters has caused nomads to leave their traditional countryside and move to the capital city Ulaanbaatar. They settled in ever expanding ger districts on the edge of the city, which now constitute about 840,000 people or 60% of the city’s population. The chapter called “Ger district life” is explicit and alarming with good photos and maps.

Ulaanbaatar was one of the monastic trading posts in the seventeenth century, not fixing its position until a century or more later. Religion and commerce thrived with temple structures being the most substantial. And a ger district formed at the edges. Throughout the era of the socialist state the city developed masterplans to determine the urban fabric, with the population exceeding the planned expectation. New arrivals inevitably settled in gers on the edge of town with no planned infrastructure.

Industry and other commercial enterprise evolved until the end of the soviet model when new developments expanded without much urban planning or control. This lack of proper control resulted in land grabs and developments including shopping malls, hotels and office space in great contrast to the ger districts.

Mongolia has rich mineral reserves – the twelfth largest copper reserves in the world and the fourth largest coal reserve – neither of which are fully explored. Huge foreign investments contribute to 40% of GDP and make for a complicated and unstable financial situation. Bailouts and national debt dependency characterise the economy that has emerged around resource extraction.

China is the source of much of this investment, as well as the main purchaser of raw materials, including coal, the proceeds from which are used to fund new power stations. Mongolia remains very vulnerable in this archetypal example of the resource curse, and struggles to take economic control of its abundant natural wealth.

Ulaanbaatar has been transformed from a relatively tightly-regulated Soviet-style city into an investment capital in thirty years, with little in the way of coherent planning of any aspect of its urban fabric. The author and his research team have proposed an alternative approach for the areas of housing and an architectural approach that draws on the ideologies of some earlier world models. This does depend on the big infrastructure being funded and in place (water, sewerage, heating and social support in terms of schools and medical care).

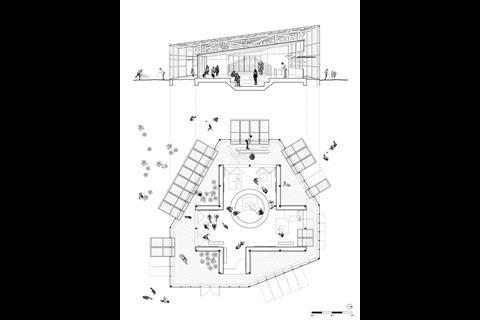

They set out their pitch first with a belief in ‘Building as Research’ in the section called ‘Prototyping’ where the author and his research team develop their thesis with a range of worked through typologies to transform and upgrade the ger (including astonishingly one called Plug-In). Some of these are built, including the Ger Plug-in housing prototype. Other built works include a waste collection point and the Ger Innovation Hub community space.

The final section is called the Incremental Urban Strategy, and includes thoughtful understanding and insight into community life. There is a manual of different housing components designed to respond to individual household needs and budgets. It may be naïve, earnest and well intentioned, but if at least some part of it is achieved, it will provide a model and exemplar for others to evaluate and continue.

The author provides a pithy critique in the concluding section ‘Framework as Method’ and clearly has a firm belief that it will work. It proposes the replacement of the masterplan in urban development and the repositioning of the architect as a critical agent. It does again place the architect centre stage, but asks for the re-conceptualising of the role they play in determining the aim and objectives of the urban development. It seeks dynamic and flexible solutions to improve quality of life.

Once again one welcomes fresh idealism. There are cultural geographers at work here with designers, and a rejection of the urbanism recognisable as glass concrete and steel real estate. There is an understanding that the process of urbanisation has changed due to globalisation and the politics and economics that go with it, but underlying this is a desire to promote a way to a better future.

Read this book and wish them well.

Postscript

Becoming Urban: City of Nomads by Joshua Bolchover is published by Oro Editions.

Katharine Heron is Professor Emerita at the University of Westminster and Founding Director of Ambika P3.

Her own interest in nomadic art and architecture arose when the University of Westminster exhibited the work of Sami architect and artist Joar Nango in Ambika P3 in 2015. His installation included the commissioning of a felt ‘carpet’ from Mongolians in Ulaanbaatar accompanied by a film of the ger city which seemed to be in perpetual twilight and occupied by dogs

No comments yet