Nicholas de Klerk reviews a new book by Edwin Heathcote that explores the way in which we invest meaning into our public spaces through inhabiting them.

At first glance, the book takes on the form of a miscellany. The sections are listed from A-Z, illustrated mostly with photographs and some with drawings, each discussing a topic or genre in some detail. Indeed, Heathcote himself invites the reader to dip into the book as an alternative to necessarily reading it sequentially in one sitting.

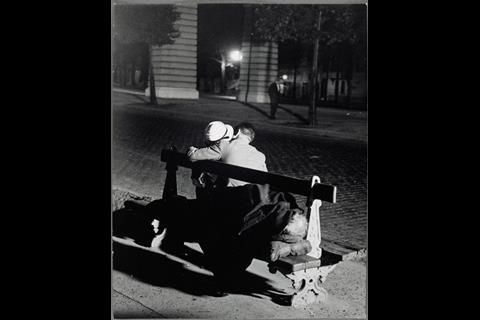

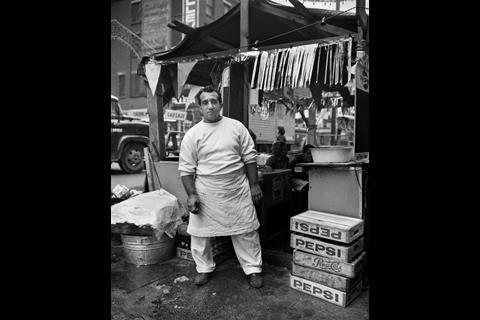

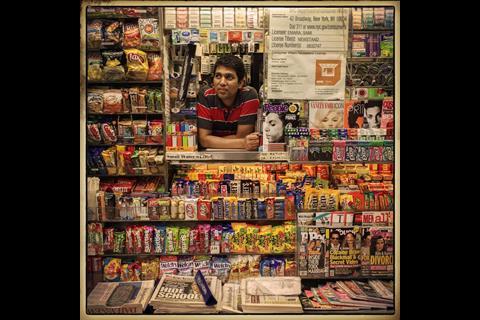

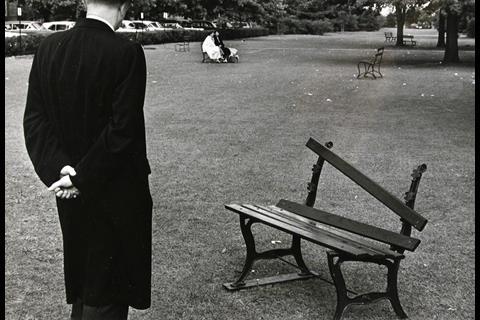

The book describes things that are both in the street – advertising, balustrading and hoarding, for example – and things that are done in the street – littering, drinking and working. This, in a sense, gets to the heart of the endeavour – describing the street as more than just space furnished with the accoutrements which populate the book. It is more akin to a space in which both objects and the people that interact with them are as actors on a stage, drawn, if not into an equivalence, then certainly into a kind of dialogue.

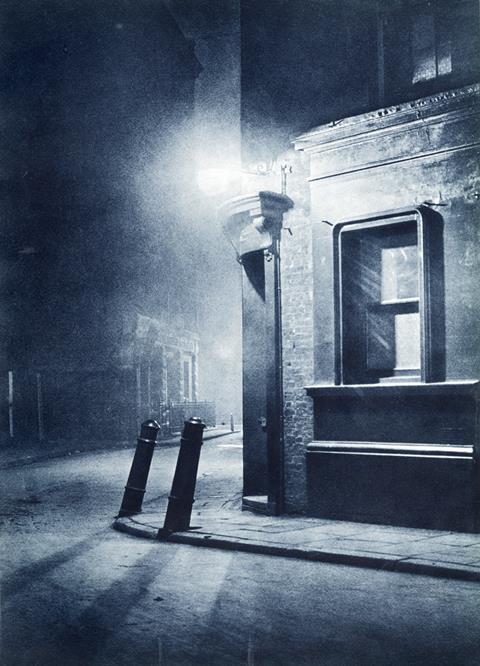

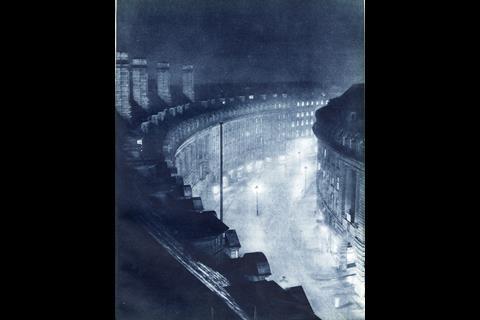

There is a signpost to this thinking in Heathcote’s retelling of the Situationists’ reimagining of the streets of late 1960’s Paris as a playground, as a beach, in the book’s introduction. This renders the sections that follow in an almost magical realist light; post boxes, telephone booths, advertising columns and more take on characters of their own, becoming legitimate narrative elements of the streets they find themselves in. Returning to the way in which the book is conceived and organised, these are things that both are and do.

If this seems perhaps a little poetic seen in the context of the visual cacophony of our contemporary streetscape, perhaps this book can act as a call to rediscover the invention and civic purpose that many of these objects once held, as imagined by the architects of Milton Keynes, for example, and their Victorian antecedents before them.

I learned a few things reading On the Street, too many to mention here. One is the existence of Thomasson, the name given in Japan to leftover fragments of demolished buildings that mark former uses and lives. These leave odd disjunctions and adjacencies that I often photograph as mnemonics to the past lives of the city in which I live.

Similarly, Heathcote describes the way in which domestic “coalhole” covers signified the UK’s wealth and industrial strength in the mid to late Victorian era. In the way in which they were designed and used, they reveal implicit social stratification and hierarchies. Now that the way in which we live in and heat our homes has changed, they have become redundant and are but a small and elegant marker of those histories.

The way in which social and historical narratives are sometimes reflected in street furniture is a particularly fascinating topic. A “culture of empire” found its way into the design of things such as ”advertising columns, fountains and even urinals” across Europe through the use of ”an exoticised language of material and ornament” which ”coincided with a genuine curiosity and interest in decorative culture from across the globe.”

If this reflected an outward-looking trading nation confident of its place in the world (perhaps one way to describe the imperial project) I wonder how the same project might be approached now in the UK’s anguished post-Brexit refashioning of itself. With traces of these histories marked throughout our cities there is a sense that these objects have the potential to embody a kind of public memory, that we would be able to relate to in individual, personal ways – such is the corporeality and utility of street furniture.

Memory is a recurring theme in the book as so many of the objects that Heathcote discusses no longer exist. When they do, they often function as a kind of urban memento mori, with the marking of their obsolescence now forming their primary function. Memory also figures strongly in the way in which On the Street also offers us a book within a book. I was reminded of the notion that ‘all writing is a form of autobiography’, which I first came across in an interview with novelist J.M. Coetzee.

In On the Street, Heathcote carefully splices intimate family histories into the text, along with photographs of himself and his parents in Paris and in London, as well as recollections of his own experiences of places and cities. This has the doubling effect of prompting you to see public spaces in a more intimate and personal way, but also to understand the way in which dwellers and visitors to cities make public space through the way in which they use it, all imperfectly choreographed by the catalogue of things that Heathcote has documented here.

Postscript

On the Street by Edwin Heathcote is published by HENI Publishing

Nicholas de Klerk is the founding director of Translation Architecture

1 Readers' comment