This CPD explores the use of Building Information Modelling which has the potential to dramatically change the process of design and construction. It is the fourth in our regular series of CPD modules for 2011 and is sponsored by Bite

Click here to take the CPD module

How to use this module: BD Reviews’ free continuing professional development distance learning programme is open to everyone who wants to develop and improve their professional knowledge and skills. These modules can contribute to your annual programme of CPD activity to help you maintain membership of professional institutions and bodies. All you have to do is read this module then take the questions via the link above or at the bottom of the page.

Building Information Modelling (BIM) is the process of creating a computer model of a building project which can be used to fully design, analyse, build, manage, refurbish and finally demolish that building.

BIM software has intelligence, enabling it to understand the many different elements of a building, such as walls, roofs, floors, windows and doors. It also understands the interrelationship between them. For example, if a wall is moved, other elements associated with it will move too, and if the size of the windows is changed, the openings in all of the walls will adjust appropriately.

The model will also include information about the construction and finish of each element and, in some instances, the resources required to construct it. The software stores these elements as parametric objects and allows designers to make global changes to the parameters, such as the size or characteristics, of any element of a building.

The use of 3D software to model buildings during the design phase is common, but most 3D modelling software treats models as collections of dumb surfaces or solids. BIM software differs because it can differentiate between these different elements and store a great deal of information about them. This intelligence enables the software to undertake many complex analyses quickly and easily.

The key to BIM is not the visual model, but the database of information that sits behind it. This enables different organisations working on the same project but using different software to store and retrieve information in a consistent, shareable format.

There is no one piece of software that will encompass all the functions required throughout the life of a building information model. Various software will contribute to and draw from the model, and so it is crucial that there is a common language that all BIM software can understand. The International Alliance for Interoperability (IAI), now the Building Smart organisation (www.buildingsmart.org.uk), developed the standard language known as IFC (Industry Foundation Classes) which is an evolving international standard (ISO 16739).

These are the two key characteristics of BIM: the software’s ability to understand the constituent elements of a building, and its interoperability.

Progress of BIM in the UK market

In the UK, most discussions of BIM relate to its use during the design stages, sometimes referred to as “little BIM”. Elsewhere, its implementation is more advanced, particularly in Scandinavia, the US, Australia and more recently South Korea. In Sydney, for example, the award-winning Ark, a 21-storey commercial building designed by Rice Daubney Architects using ArchiCAD, was designed, constructed and handed over for facilities management as a building information model.

Several contractors and consultants in the UK market are now beginning to implement a BIM strategy for the design and analysis functions of the process. Some contractors are also looking at estimating functions, and using the BIM model for 4D (time) and 5D (cost) resource allocation during construction phases.

These latter functions are considerably more advanced in the US with Vico software (originally derived from ArchiCAD). Some consultants in the UK are bringing together architectural and structural models and a very few have also integrated MEP models. Currently, structural models are more likely to come from constructional steelwork subcontractors than from design practices. The former have nearly all used software to model and cut the structural members for many years, ensuring their off-site construction is correct before they get to site. Structural models from both Tekla and AceCAD products can be exported as IFC models for importing into architectural BIM software.

Benefits of using BIM

In a traditional design process 2D drawings are passed between consultants and manually checked. With BIM, intelligent models of the building can not only be passed between consultants but combined into a single model and checked with clash-detection software to ensure coordination. This is not only faster but reduces the chance of human error, as information does not have to be continually recreated.

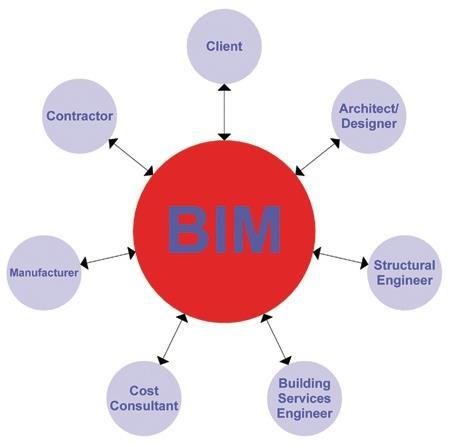

BIM also aids clearer communication to everybody involved in a project: the client, other consultants, the contractor, subcontractors and operatives. The design model can then be passed to contractors and subcontractors for tendering and project and resource planning. Further information about construction costs and programmes can be gathered and stored, to inform more accurate estimating in future.

The implementation of BIM throughout the construction process presents challenges but has the potential to dramatically reshape the industry. It will undoubtedly be necessary to examine relationships and responsibilities between the various parties involved. Some of these issues were explored in the excellent series of free Directors Briefings held in London in November 2010.

The next series will take place in Birmingham in June. http://info.graphisoft.co.uk/directors_bim/

Other benefits include:

- Improved design process: better and continuous evaluation of the design in terms of aesthetics, performance and brief fulfilment (offered by products including Solibri, Trelligence, Navisworks)

- Better communication of the design to the client and others at all stages of the process (eg; VBE, Navisworks)

- Coordination of construction and specification information, for example with links to national building specifications (eg: ArchiCAD, Revit)

- Environmental assessments: analysis for thermal performance, lighting, fluid dynamics, environmental impact assessments etc

- (eg; EcoDesigner, IES, Design Builder, Ecotect)

- Quicker and easier design revisions, as parametric elements are more flexible and easier to modify at any stage than traditional CAD (eg; ArchiCAD, Revit)

- Manageable consistency of standards across a project, as it is easier to maintain consistency with parametric elements

- (eg; ArchiCAD, Revit)

- Easier and more accurate scheduling of information at all stages (eg; Solibri, ArchiCAD, Revit)

- Quantity take offs (eg; Vico, RIB)

- More accurate tendering processes (eg; Vico)

- Project planning and resource allocation (eg; Vico, Synchro)

- More accurate construction planning (eg; Vico, Synchro)

- More efficient construction phasing with less wastage (eg; Vico)

- Links to facilities management (eg; ArchiFM and other SQL-based systems)

Evaluating BIM software

The BIM software in use in the design and analysis phases is the most mature, and some has been in use for more than 20 years, since before the process was known as BIM.

When choosing software, it is essential to carry out due diligence investigation and look afresh at the whole market.

If your practice’s current software publisher suddenly announces that they now “do BIM”, do not automatically choose that product.

BIM has become something of a buzzword and some software publishers assume they can simply bolt on BIM capability to existing products. Due to the fundamental intelligence required of BIM software, this is unlikely to result in a product that is efficient or easy to use, and will not necessarily be easier to implement as it requires a completely different strategy from CAD.

There are relatively few software packages that have been designed as BIM software from the ground up. ArchiCAD by Graphisoft (now owned by Nemetschek) and Revit (now owned by Autodesk) are two well-used packages which will create true building information models.

The most effective way to evaluate software is to run a pilot project. Most BIM products offer a limited trial licence and some vendors offer priority support for these trials.

Another approach is to do your next project using BIM. This can be a steep learning curve, but by taking advantage of the professional training and support offered by software vendors, you may be able to achieve more than you expect. BIM software vendors may offer agreements which will support the use of software licenses until the end of the pilot, reducing your risk to manageable proportions.

Throughout the pilot project you will inevitably discover aspects of the software that work for you and others which don’t. The task is to balance the pros and cons to arrive at a solution that suits your organisation and the way it operates.

At the outset, you should establish the principles on which you will judge the outcome. You should consider:

- How BIM could benefit the organisation and how you will measure this comparatively

- Nominating a senior person as the BIM pilot champion to oversee the project and report back to the rest of the senior team

- Using a typical project of a similar type for each pilot, or running the same project in parallel

- Choosing team members who are enthusiastic about BIM and up for the challenge

- Undertaking adequate training or you will not be able to understand the software sufficiently to evaluate it comprehensively

- Using support services provided by the vendor to obtain advice on setting up the project template

- The extent to which existing processes will need to change

- The direct and indirect costs of implementing BIM

When evaluating the software, consider:

- Does it suit your design methodology?

- Is it sufficiently flexible in the design stages?

- Is it straightforward and easy for staff to learn?

- Can it produce the documentation required throughout the different stages?

- Does it have enough depth for all the information you need to store, and how far does it allow you to use this information?

- Can your company standards be applied?

- Does it have a comprehensive library of parametric objects?

- Does it communicate well through the standard language IFC with other BIM software?

- Try exporting an IFC file and then re-importing it – does it look the same?

Using BIM

Implementing a BIM strategy in an organisation inevitably means changing established processes to take advantage of the benefits. The first step to using BIM is to decide how this strategy will be implemented.

The second step is to choose the correct software and obtain training in how to implement and use it. For example, architects who will be using the software must understand that although it might look like Computer Aided Design (CAD) software, it is fundamentally different. BIM software can be used in the same way as CAD, but that would be a waste of its functionality. It is also essential that those people within a firm responsible for managing work-flow and productivity under-stand how to implement BIM.

How to use this module

BD Reviews’ continuing professional development distance learning programme can contribute to your annual CPD activity and help you maintain membership of professional institutions and bodies. To complete this CPD, read the module and click here to take the test online. If you experience any problems veiwing the test online, contact bdreviews.cpd@ubm.com

MODULE 4 DEADLINE: May 28 2011

Privacy policy

- Information you supply to UBM Information Ltd may be used for publication and also to provide you with information about our products or services in the form of direct marketing by email, telephone, fax or post. Information may also be made available to third parties.

- “UBM Information Ltd” may send updates about BD CPD and other relevant UBM products and services. By providing your email address you consent to being contacted by email by “UBM Information Ltd” or other third parties.

- If at any time you no longer wish to receive anything from UBM Information Ltd or to have your data made available to third parties, please write to the Data Protection Coordinator, UBM Information Ltd, FREEPOST LON 15637, Tonbridge, TN9 1BR, Freephone 0800 279 0357 or email ubmidpa@ubm.com

Downloads

Design resources diagram

Other, Size 0.2 mb

2 Readers' comments