- Home

Heinz Isler’s Norwich Sports Village given grade II listing

Heinz Isler’s Norwich Sports Village given grade II listing Niall McLaughlin named winner of RIBA’s 2026 Royal Gold Medal

Niall McLaughlin named winner of RIBA’s 2026 Royal Gold Medal ‘Getting gateway 2 approval now much closer to stated 12 weeks,’ Building Safety Regulator boss says

‘Getting gateway 2 approval now much closer to stated 12 weeks,’ Building Safety Regulator boss says Allies and Morrison and Stanhope appointed to masterplan redevelopment of Paddington hospital site

Allies and Morrison and Stanhope appointed to masterplan redevelopment of Paddington hospital site

- Intelligence for Architects

- Subscribe

- Jobs

- Events

Events calendar Explore now

Keep up to date

Find out more

- Programmes

- CPD

- More from navigation items

‘Sustainability’ is a dangerous mirage

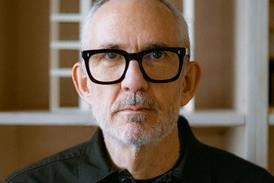

By Owen Hatherley and Owen Hatherley Owen Hatherley Owen Hatherley2009-12-11T00:00:00

Even in Dubai, the language of greenwash is used to distract us from the real design issues

This is premium content.

Only logged in subscribers have access to it.

Login or SUBSCRIBE to view this story

Existing subscriber? LOGIN

A subscription to Building Design will provide:

- Unlimited architecture news from around the UK

- Reviews of the latest buildings from all corners of the world

- Full access to all our online archives

- PLUS you will receive a digital copy of WA100 worth over £45.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

Alternatively REGISTER for free access on selected stories and sign up for email alerts

- © Building Design 2023

- Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- About BD

- Contact BD

- Advertise

Site powered by Webvision Cloud