Birmingham has a once in a generation opportunity to repair the damage done to its historic markets quarter in the 1970s, but risks further harm if it simply gentrifies the area, writes Joe Holyoak

In 1973, eight hectares of historic streets and buildings adjacent to Birmingham’s city-centre Bull Ring markets were wiped from the map. They were replaced by the new wholesale market – big, single-storey sheds inside a walled stockade: a lifeless, anti-urban obstacle to movement.

In 2012, working for the retail market traders who wanted the wholesale markets to remain next door to them, I designed a scheme showing how the area could be redeveloped permeably while retaining the wholesale markets. My proposal was to rebuild in a different form on a smaller footprint, together with other land uses. But the city council was committed to the wholesale markets’ removal, and the proposal went nowhere.

In 2018 the wholesale markets were relocated to new sheds four miles away, near to Villa Park. The empty site, which will accommodate meanwhile activities of basketball and beach volleyball in this summer’s Commonwealth Games, is now part of the 14-hectare mixed-use Smithfield development site.

Public space is expensive to make, and does not earn any money

The current masterplan was prepared in-house by the city council in 2016. It is a good plan, largely restoring the lost joined-up street network, providing new buildings for the Bull Ring retail markets and including 2,000 dwellings among other uses. The multinational Lendlease is the chosen developer, and it has appointed a number of architects, who are now designing phase one.

This includes the new retail markets, other buildings including 600 dwellings, and a large new square. The inclusion of public space in the first phase is unusual, and encouraging.

Public space is expensive to make, and does not earn any money. Major public space is often left to a later phase of development, after income-earning buildings are built and occupied.

Six firms of architects are involved: four London practices – Haworth Tompkins, dRMM, RCKa, and David Kohn Architects. And two small West Midlands practices – Minesh Patel Architects and Intervention Architecture. Prior + Partners are masterplanners and James Corner Field Operations are the landscape architects.

In phase one, the six architects are combined in design teams for each of the five buildings. It is a collaborative design exercise reminiscent of Argent’s mostly-successful Brindleyplace development, which started nearly 30 years ago. It has been surprising that the success of Argent’s groundbreaking scheme has not led to other similar team projects in the city until now. Smithfield will be measured against the achievement of Brindleyplace.

David Kohn Architects, working with Eastside Projects (a local public art organisation), is responsible for the design of the new retail markets.

The Bull Ring market stallholders have not had happy past experiences of city centre redevelopment. When the 1963 Bull Ring shopping centre was built, together with the Inner Ring Road, wrecking the historic street pattern, the open-air traders found themselves squashed between subways and overshadowed by a highway flyover.

When the failed 1960s shopping centre was replaced by the ineptly-named BullRing in 2003, the traders were pushed farther away from the city core, beyond St Martin’s parish church. Now, although the open-air market will stay in the same place, the Indoor Market and the Rag Market will be relocated farther away still from the city core. They will be on the edge of the new square; perhaps some compensation for their displacement.

Lendlease’s aspiration appears to be to make the place glamorous and move it upmarket

As sometimes happens, a fake history is being invented for the market redevelopment. The name Smithfield was imported from London by the Birmingham street commissioners in 1817, and later given to the 1880 wholesale meat market building; a fine building which, to avoid its possible listing, was demolished by the council on a bank holiday in the great 1973 clearance.

To add to the confusion, Lendlease’s publicity claims that “the original Smithfield markets were destroyed during World War II…” But what the Luftwaffe bombed was actually the 1835 Market Hall in the Bull Ring. And the adjacent open-air market has always been known as the Bull Ring market.

I suspect that Lendlease’s motivation for resurecting the Smithfield name, like that of the earlier street commissioners, is to acquire by association a pedigree with a metropolitan resonance.

One critical issue is how the open-air market traders’ continuity of operation will be maintained during the rebuilding. Currently, there seems to be no answer to this. Their economic prosperity has been declining over the past 40 years and they have not been well served by their landlords, the city council. Any interruption of trading could further seriously damage their economic viability.

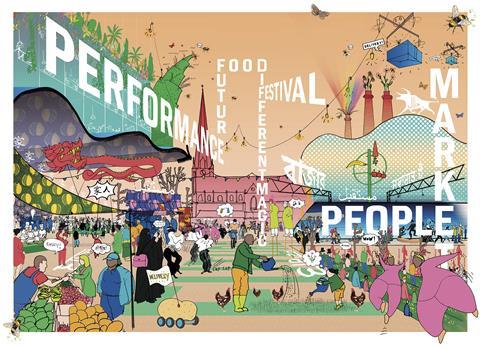

Lendlease’s aspiration appears to be to make the place glamorous and move it upmarket – “an international creative and cultural destination” – not just a place to buy bananas and carrots. Is this realistic while also maintaining the historic outdoor markets? I doubt it.

Better surely to concentrate on making a user-friendly and convenient food market, especially for the poorer and more elderly residents of the city who depend on it.

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham.

No comments yet