Sponsored by Tobermore, this CPD module explores how to balance aesthetics and functionality when designing hard landscaping for mixed-use developments. We will also take an in-depth look at issues to consider when specifying paving

Hard landscaping is an important part of the design of any mixed-use development, and choosing the right paving is crucial to the creation of the appealing public realm that is so vital to the success of mixed use.

Learning outcomes

- Recognise the role of landscape design in the success of mixed-use developments.

- Understand key trends in hard landscaping design.

- Learn about the standards that apply to paving.

When specifying hard landscaping materials, there are many factors to consider: product performance, durability, cost, aesthetic impact, compliance with regulations and standards, lead times, sustainability, and manufacturer support. We will consider these in detail, but first we will look at some of the broader issues and trends affecting landscaping.

Mixed-used developments

A mixed-use development is one that combines two or more distinct land uses – residential, commercial, office, and institutional spaces, say – within a single building or area. Mixed-used developments can be vertical – where a single tall building accommodates different uses on different floors – or horizontal, with a range of buildings on the same site that each fulfil a separate purpose.

Post-war planning in Britain often featured large, single-use buildings, such as shopping centres, which subsequently faced criticism for failing to provide the diversity and flow offered by traditional town centres. Today, the benefits of mixed used are recognised, and this form of development is encouraged in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Advantages of mixed use

For residents, mixed-use developments offer better access to services and reduced car dependency. Higher densities also make public transport more viable. Mixed-used developments can be vibrant places with activity throughout the day, and the improved opportunities for social interaction can help build community cohesion. The right mix of housing types, tenures and amenities can create inclusive communities.

Economically, mixed use has huge potential, offering diverse revenue streams for developers and operators. The creation of characterful places with attractive public realm encourages footfall in commercial areas, supporting small and local businesses. At the same time, natural surveillance in public areas can improve safety.

Mixed-used communities can also be more compact, which can equate to increased sustainability through more efficient land use and a lower carbon footprint from transport.

Challenges of mixed use

The challenges of mixed use include complex management and ownership structures, longer phasing and relatively complicated upfront planning and investment, which make for more challenging viability models for developers.

The maintenance demands of the public realm, shared areas and services can present ongoing challenges. Waste and loading areas require careful design and screening. In addition, there can be conflicting needs between different uses, for example night venues and residential.

Good practice

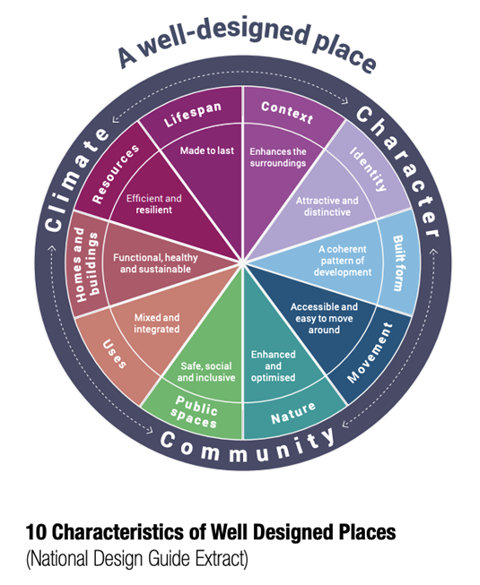

Good practice in the design of mixed-used developments is covered in various government guidance documents, such as the National Design Guide, a government guidance publication that sets out the 10 characteristics of well-designed places and aids understanding of what good design means in practice.

The Department for Transport’s Manual for Streets (2007) and Manual for Streets 2 (2010) – guides that redefined how streets should be planned and designed, shifting the focus from traffic movement towards placemaking, people, and communities – are still useful reference sources despite being quite old. A revised combined edition has been proposed.

Several of the documents that the Greater London Authority (GLA) has produced on the implementation of the London Plan are worth a look regardless of where you are building. Check out: Housing Design Standards (London Plan Guidance), London Housing Design Guide (Interim Edition), Small Site Design Codes (London Plan Guidance) and Expanding London’s Public Realm Design Guide.

The guidance makes it clear that there are many factors to consider when designing liveable mixed-used developments – and aiming to build vibrant communities – such as:

- Context and character – current thinking emphasises placemaking that is responsive to its context rather than one-size-fits-all.

- Walkability – streetscapes should be pedestrian-friendly to encourage walking and reduce reliance on cars, with a shift from car-dominated layouts to “15-minute neighbourhood” principles.

- Accessibility – how can the development be made accessible to all?

- Public transport – convenient access to public transport and bike lanes is vital to connect residents to the wider community and reduce car use.

- Green spaces – good placemaking emphasises quality public spaces: green spaces that are safe, social, usable and contribute to health and wellbeing, as well as green infrastructure, trees and wildlife habitats.

- Community facilities – a mix of facilities, from schools and GP surgeries to playgrounds and public seating areas, is crucial to meet the varying needs of residents. Providing places where people can mix is crucial for building community.

- Employment opportunities – where will the people who live in the housing work?

- Sustainability – circularity and carbon use are now key indicators for all construction projects.

- Stewardship – good development design will plan for maintenance, manageability and long-term management.

Mixed-use developments can create sustainable, vibrant, walkable communities, but success depends on careful design, phasing, management, and community involvement and alignment. Mixed used works best when the public realm is prioritised and where long-term stewardship is carefully planned for.

The role of landscape design

Landscape design has a vital part to play in delivering the attractive public realm that is key to the success of mixed use. The Landscape Institute defines landscape design as “the holistic process of shaping the natural and built environment to create desirable places for people to live, work and play and environments for plants and animals to thrive”.

In mixed-use developments, good landscape design can help:

- Bring a sense of coherence to the disparate spaces/structures with their distinct functions

- Deliver safe, inclusive and accessible spaces

- Improve the legibility of the development – how easily spaces are understood and navigated – and encourage full use of amenities

- Maximise usable land on tricky sites

- Create beautiful places – shape visual composition, atmosphere, and a sense of place through the choice of materials and use of light, planting and texture to evoke mood, seasonality, and continuity with local character

- Build in sustainability and biodiversity.

Landscape design involves not only hard landscaping – the hard surfaces and structures in a landscape design such as paths, walls, patios and driveways – but also soft landscaping, which covers the vegetative elements such as plants, trees and grass. The hard landscaping is often thought of as the bones or framework that gives the landscaping its structure. It is generally permanent and lower-maintenance, while the planting will often require ongoing higher levels of maintenance.

Design trends

There are many external influences shaping trends in the design of mixed-use developments, and their outdoor spaces in particular. Here are some of the key ones:

- Flexibility – more interior and exterior spaces are being designed to be flexible and easier to reconfigure in the hope this will make them more resilient to future social changes.

- Resilience – outdoor spaces are being designed to cope with an increasingly extreme climate. Think: drought-resilient planting and sustainable drainage systems (SUDs).

- Tech – smart and connected spaces will increasingly leverage technology to enhance convenience and resource management, while the use of both augmented and virtual reality is on the rise.

- Wellness – amenities are increasingly expected to promote physical and mental health and wellbeing.

- Biodiversity and rewilding – a shift from purely ornamental landscaping to ecologically functional spaces that support local biodiversity, pollinators and habitat connectivity

- Social interaction – outdoor spaces are increasingly designed as social infrastructure, not leftover green spaces: shared gardens, pocket parks, play streets and community food-growing areas, as well as places for informal encounters and programmed events.

- Inclusivity and accessibility – there is a strong movement towards universal design, ensuring spaces are accessible and enjoyable for all ages and abilities. Meanwhile, co-design with communities is becoming standard practice.

- Passive design for outdoor comfort – shading, cooling through planting, orienting to prevailing winds, and heat mitigation through green infrastructure such as shade trees, reflective surfaces and water features are all on the rise, and so is design that supports year-round use like canopies and windbreaks.

- Productive landscapes – edible planting, community orchards and rooftop gardens are popular, supporting local food resilience.

- Data-driven design and performance monitoring – there is an increasing use of sensors, digital twins and performance monitoring to track environmental, social and usage outcomes.

Biodiversity net gain

In England, biodiversity net gain (BNG) is mandatory under schedule 7A of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, and developers must deliver a BNG of at least 10%, although the local planning authority may require a higher figure. The idea is that a development will result in more or better natural habitat than there was before development.

The landowner is legally responsible for creating or enhancing habitat on site or elsewhere, as well as for managing that habitat for at least 30 years. Developers may purchase offsite BNG units if delivery on site is not feasible. Paving can contribute to BNG where it is permeable, integrates vegetation and soil, supports SuDS, provides micro-habitats, uses reclaimed materials, or forms part of a connected green infrastructure strategy.

Hard landscaping

When it comes to specifying paving there are a wide range of factors to take into consideration, including performance, durability, cost, aesthetic impact, compliance with regulations and standards, and sustainability.

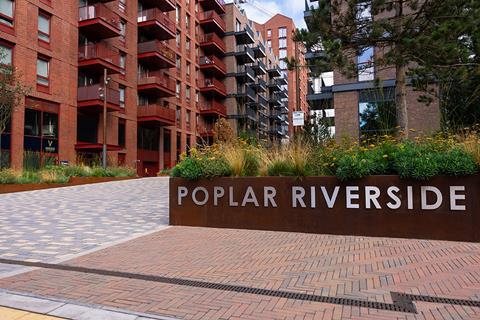

Paving is important because it creates the kind of open community spaces that are becoming a key factor in attracting discerning customers to developments – and the appealing public realm that is crucial to mixed-use success. Given the large areas that paving will cover in many developments, the colour and texture contribute greatly to the site’s overall visual appearance. Specifying paving products, edging, kerbing and steps with the right look to complement the project’s aesthetic goals is vital.

A large array of options are available, including concrete flag paving, concrete block paving, pressed concrete slabs, reconstituted stone paving, natural stone paving (such as granite, sandstone, limestone, York stone, slate, porphyry), clay pavers, asphalt, resin-bound paving, resin-bonded paving, loose gravel, self-binding gravel, porcelain or ceramic paving, timber decking, composite decking, metal paving and gratings, recycled rubber paving, recycled plastic or composite paving, geopolymer or low-cement paving systems.

Regulations and standards

There are many regulations and standards that paving may need to comply with. One example is the rules regarding SuDS, which are covered in detail in a previous CPD module sponsored by Tobermore.

A whole host of British Standards (BS) and European Standards (EN) apply to paving. Some cover the manufacture of products, others installation – below are just some of the relevant standards.

|

BS 7533-101:2021 |

Pavements constructed with clay, concrete or natural stone paving units – code of practice for the structural design of pavements using modular paving units |

|

BS 7533-102:2025 |

Pavements constructed with clay, concrete or natural stone paving units. Installation of pavements using modular paving units – code of practice |

|

BS 7533-11:2003 |

Pavements constructed with clay, natural stone or concrete pavers – code of practice for the opening, maintenance and reinstatement of pavements of concrete, clay and natural stone |

|

BS EN 1338:2003 + AC:2006 |

Concrete paving blocks. Requirements and test methods |

|

BS EN 1339:2003 + AC:2006 |

Concrete paving flags. Requirements and test methods |

|

BS 7932:2003 |

Determination of the unpolished and polished pendulum test value of surfacing units |

|

PD CEN/TS 15209:2021 |

Tactile paving surface indicators produced from concrete, clay and stone |

|

BS 8300-1:2018 |

Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment – external environment. Code of practice |

|

BS 8300-2:2018 |

Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment - buildings. Code of practice |

Standards are not laws in themselves, but they can become legally enforceable in specific contexts, if referenced in law, regulation or contract. They are often cited in Building Regulations approved documents, contracts, planning conditions, health and safety legislation via approved codes of practice (ACOPs). If a British Standard is referenced in a regulation or contract, then compliance becomes legally required. Standards are also used as evidence of best practice in the event of disputes or litigation.

European Standards have been adopted as BS EN standards in the UK through the British Standards Institution (BSI). They are still valid in the UK, despite Brexit, because the BSI remains a member of CEN (the Comité Européen de Normalisation, the European Committee for Standardisation – the main European standards-setting body). They have the same legal status as British Standards: that they are voluntary unless mandated, and binding if referenced in UK law or contracts. The standards for concrete paving blocks and flags BS EN 1338:2003 and BS EN 1339:2003 are under revision.

Regional, local and estate design codes are become increasingly common and cover outside areas and public spaces as well as building design. They will typically have something to say about the following aspects of hard landscaping:

- Paving and surfacing materials – material palette, finishes, permeability, quality hierarchy

- Kerbs, edges, boundaries – material consistency, height, form, treatment guidance

- Street furniture and lighting – co-ordination of styles and materials

- Drainage and SuDS – requirements for permeable surfacing and integration

- Accessibility – tactile paving, gradients, clear routes

- Character and identity – use of local materials, coherence with setting

- Maintenance – expectations for durability, repair, stewardship.

Slabs or blocks?

Whether you choose paving slabs or blocks will depend primarily on the traffic level. Paving slabs give a clean, modern contemporary aesthetic with minimal joints, and are best suited to areas where the traffic is mainly pedestrian. The larger units make for faster laying. Designers will need to decide whether they want to lay pavers in a stack or stretcher pattern.

Block paving provides strength and durability. The smaller units are better at handling movement and loads. Block paving is a good choice anywhere vehicles will use – such as driveways, service roads and parking spaces – as well as paths that take heavy foot traffic and places where the ground is prone to movement or frost. Block paving allows for patterns, such as herringbone or basketweave, as well as neat borders and curves. If a block cracks or dips, it can be popped out and replaced easily. New developments include blocks with anti-shift ridges on the sides for extra stability, such as Tobermore’s Tetralock.

Sub-base

The level of traffic will also influence what kind of sub-base is needed to give paving the required support. Refer to BS 7533 for sub-base design and the most suitable product size for each application. Tobermore has a sub-base specifier tool to make the job easier.

Sustainability

Sustainability plays a large part in all design and purchasing decisions in the built environment today. The lowest carbon paving is reclaimed stone. Other lower carbon options are local stone or paving that contains some form of recycled aggregate. Concrete pavers and blocks typically contain more embodied carbon than natural stone and less than asphalt, though there are a great number of variables so you should always get specific figures for individual products. However, transport distances make a big difference: natural stone transported from the other side of the globe is likely to have higher carbon than concrete pavers, for example.

The cement in concrete is a high-carbon material. While manufacturers can impact embodied carbon by using renewable energy, it is hard to decarbonise cement comprehensively because a big share of emissions comes from the chemical reaction, not the energy used. Manufacturers are working on lower-cement concrete products with alternative binders such as ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), fly ash (PFA or pulverised fuel ash), limestone calcined clay cement and limestone cement. These products offer various degrees of decarbonisation but there are supply issues with most.

Re-use is another avenue with potential. Theoretically concrete pavers can be reused at the end of their life, but few facilities accept and process pavers for reuse. In addition, cement mortar beds, cementitious pointing, resin joints or beds and bitumen bonding make it difficult to lift slabs easily. The future lies in non-adhesive beds and dry jointing. Cities could use a “materials depot” model, like the Amsterdam material passport system, to support circular use of materials. As mentioned already, permeable paving as part of a SuDS scheme is a good way to meet sustainability targets using paving.

The heat island effect is something else to consider. This is the phenomenon whereby urban areas become significantly hotter than nearby rural or natural areas because of all the dark, heat-absorbing surfaces – like asphalt roads and roofs – and a lack of trees and soil to cool the air. Light coloured concrete paving and natural stone, planting mixed with paving, and permeable paving can all help mitigate the effect.

Sustainability credentials

When it comes to sustainability credentials, look for manufacturers that are BES 6001 certified. This is a BRE certification scheme for the responsible sourcing of construction products that verifies environmental, social, and governance performance across the supply chain. Environmental performance declarations (EPDs) – third-party verified lifecycle environmental impact reports – will also give you information about aspects of products’ manufacture, such the use of renewable power, recycling of water, and ethical sourcing.

Paved areas may have to be assessed against the BREEAM sustainability assessment and certification framework if they are part of projects being assessed for BREEAM certification. External paving can support BREEAM requirements through responsible sourcing (BES 6001 or equivalent), EPD provision, low carbon materials, and permeable or SuDS-compliant design where applicable. Similarly, paving can contribute to LEED points by supporting heat-island reduction, stormwater management, responsible sourcing, recycled content, EPDs and habitat-friendly design strategies.

Quality and durability

The more durable the product, the less maintenance will be required, reducing ongoing costs. Also, replacement of products will be less frequent, saving further capital costs. For extra reassurance, some manufacturers offer product guarantees.

Durability test

The wide wheel abrasion test (EN 1338: Annex G) measures paving slab durability. A sample slab is pressed against a wide rotating steel wheel while an abrasive material (such as sand) is fed between the wheel and the sample. The result shows how much of the slab is worn away, recorded as mm³ of material lost – lower numbers indicate high durability. EN 1338 requires ≤ 23cm³ volume loss.

Freeze-thaw test

The resilience of paving in the face of frost is measured against EN 1339 using a freeze-thaw test that involves slabs being saturated and salted then cycled through freezing and thawing. Again, the amount of material lost from the surface – scaling – is measured and reported as mass loss per square metre (kg/m²) after x cycles. The smaller loss the better and a typical acceptance requirement might be ≤ 1kg/m² after 56 cycles (for severe exposure).

Slip test

Slip resistance, another important quality, is usually measured using something called the pendulum test. A spring-loaded swinging arm (the pendulum) with a rubber slider at the bottom swings across the surface of the paver, and the slider briefly contacts the surface. The slider loses energy due to friction, and the machine measures the energy loss. Surfaces are commonly tested wet. Results are reported as a pendulum test value (PTV). Higher friction = higher PTV = lower slip risk. A PTV ≥36 wet is generally considered safe.

Efflorescence

A different performance challenge is efflorescence, a frequent problem for builders working with bricks or concrete. It is a white, powdery or crystalline deposit that appears on the surface of bricks, concrete, stone or mortar when water dissolves salts within the material then moves to the surface and evaporates, leaving the salts behind. While it is not possible to completely eradicate efflorescence from concrete paving, vapour curing for at least 12 hours during manufacture can help reduce the problem.

Costs

Three main material paving types that are considered for housing developments: concrete, natural stone, or porcelain. Concrete paving is generally the cheapest, followed by natural stone then porcelain.

The four main contributors to total cost, with a rough percentage cost, are:

- Materials 35%

- Installation 35%

- Excavation 20%

- Waste removal 10%.

Another factor to consider is lead times. Concrete paving is generally available with shorter lead times than natural stone. When delays on site can prove costly, product availability can have a secondary bearing on costs.

Product support from manufacturers

Some manufacturers provide both pre- and post-specification support. They can advise on the most cost-effective and efficient ways to use products based on site plans. Some also offer on-site toolbox talks to explain best practice on installation.

Maintenance

Maintenance of paving is important to keep up its visual appearance and functionality. Manufacturers’ guidance should be followed to ensure paving is cleaned, maintained and repaired in the best way to ensure its longevity.

Tactile paving

Another important aspect of paving design is the use of tactile paving to aid visually impaired and blind pedestrians. The colour and tonal contrast of tactile paving slabs is covered in the Department for Transport’s (DfT) Guidance on the Use of Tactile Paving Surface. Approved Document M (ADM) of the Building Regulations also has some guidance on the use of tactile paving surfaces. It highlights the fact that the Equality Act 2010 imposes additional duties on service providers and employers regarding adjustments to physical features that may disadvantage a disabled person. Complying with ADM does not guarantee compliance with the Equality Act, so specifiers need to be fully aware of their obligations under the Equality Act.

Here are some examples of common tactile paving use:

- Red blister (raised domes) paving at pavement edge – signal-controlled crossing

- Buff blister paving at pavement edge – uncontrolled crossing

- Corduroy paving (raised ridged bars running across walking direction) – hazard or need to stop and check: this is used to warn of, for instance, the top or bottom of a set of stairs; escalators or lifts; and changes in level.

- Guidance or directional paving (long raised bars aligned with walking direction) – a safe route or direction to follow in open spaces.

Local guidance can differ from national guidance, particularly around the use of different coloured tactile pavers. Also, real-world use of tactile paving has not always followed the (perhaps confusing) rules given in Guidance on the Use of Tactile Paving Surface. (A report, Accessible Public Realm: Updating Guidance and Further Research, commissioned by the DfT looks at common problems and proposes possible modifications to the system.)

Another source of useful information is BS 8300:2018 Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment – external environment – code of practice. This focuses on maximising inclusivity for a wider range of visitors, beyond the requirements of Building Regulations. Meeting BS 8300 is not a legal requirement, but it does provide specifiers with useful examples of best practise for maximising accessibility and inclusion.

Appearance

Concrete is a cheaper alternative to natural stone, but the look of concrete paving products has improved greatly over the years. Concrete paving suitable for pretty much every context – from aged blocks that can recreate historic herringbone paving to pavers with granite aggregate in a whole range of shades reflecting the different colours of natural granite – is now available. Some manufacturers offer online tools to help designers visualise the effect of different paving colours and finishes in context.

Here are some trends in contemporary paving design:

- Nature-integrated and biodiversity-supporting surfaces – such as stone setts with soil, moss or low plants in joints; planting pockets and tree pits embedded in paving grids; micro-habitat-friendly textures and vegetation pockets in paving; tree-root-compatible substructures.

- Design that centres circularity – futureproof modular designs; reused materials; repairable systems, such as lift-and-reuse block systems; blended reclaimed and new systems.

- Sensory quality and craft – textural, tactile and crafted finishes such as bush-hammered and flamed stone; washed and exposed aggregate concrete.

- Civic identity – revival of traditional designs such as herringbone; slab with sett borders; embedded wayfinding and graphics.

- Earth-toned materials – buff, sand, taupe, warm greys; soft tonal blends and variations rather than stark contrasts.

- Move towards universal design – including neurodiversity-aware detailing (calm patterns, lighting); and designing out trip lips and wobble zones.

- Blurred boundaries – paving dissolving into planting; gravel and stone hybrid edges and boardwalk transitions; grasscrete and similar cellular systems.

Final thoughts

These are the long-term trends, but cost-effective, attractive concrete paving, backed by EPDs, manufacturer guarantees and BRE 6001 certification, currently remains a key component of the hard landscaping in most mixed-use developments.

Please fill out the form below to complete the module and receive your certificate.