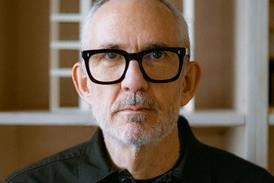

Martyn Evans explains his big plans for the historic Devon estate, inspired by its pioneering founders and using today’s best architects

I have a new job. At the beginning of the month I started work as development director at the Dartington Hall Estate in Devon. In the countryside. Having spent the last 20 years developing projects in town and city centres, it’s quite a change.

The Dartington Hall Estate is 1,200 acres of beautiful countryside where, almost 100 years ago, a visionary couple came to make a home in a 14th-century manor house and start an experiment in rural enterprise and community. The world they inhabited had just emerged from of a period of devastating war, was experiencing huge economic insecurity and massive technological and societal change. Sound familiar?

Their response then was to create the kind of place that offered its community a life of well-being by building homes with security of tenure, starting businesses to create secure jobs, providing the means for a good education for its children and offering access to a full and inspiring cultural life. They did this by building.

Over the 50 years that Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst lived and worked at Dartington, they built an extraordinary range of buildings from arts & crafts houses to modernist masterpieces by the Swiss-born American architect William Lescaze. They hired the famous heritage architect William Weir to restore the medieval hall turning the teams of craftsmen and women he gathered together into a series of building, carpentry and design operations that became self-sustaining, independent businesses. The schools they commissioned from architects Delano and Aldrich and Oswald Milne were the kind of buildings designed as much to lift their students’ hearts as expand their minds. I have in my charge 42 listed buildings, two scheduled ancient monuments, a large working farm and a medieval barn converted into a cinema in 1934 by Walter Gropius.

What’s left now is a beautiful but somewhat sad legacy of decades of underinvestment in the buildings and the operations that remain in them. But to walk the estate is to understand how an extraordinary architectural project came to be the catalyst for enormous economic and social development success. I think I have the best job in the world – to bring the place back to life and resurrect the social and cultural experiment that seems so inspiring and relevant to the world in 2017. And I’m going to learn from the Elmhirsts’ lessons by employing a team of clever architects to help me do it.

It won’t be easy. But I’ve never been afraid of hard work or afraid to write the kind of briefs that frighten the crap out of design teams, engineers and quantity surveyors. I’m not going to apologise for asking the impossible, challenging dogma and seeking solutions to problems that appear insuperable.

Take housing… The economics here are scary. My local area is the English borough with the second highest disparity between average earnings and average house prices. For a family on an average household income, the kind of mortgage that’s easily available means they have to look for a house that costs around £200,000. On the market that house is currently for sale for north of £300,000. So, what’s to do?

Can we design our way out of the problem? Can we find an innovative way of funding that makes it work? Can we find a new shared-ownership or self-build model that allows homeowners to share in the development of their home? Any or all of those might provide an answer but we’re only going to find out by challenging the status quo, ignoring those who say “can’t be done” and staying up all night.

I’ve spent hour after hour over the last 20 years sitting in seminars and conferences listening to architects share genius ideas to save the world… with other architects. I’m excited about being able to prise some of those ideas out of their PowerPoint prisons and set them free. I’ll let you know how I get on.

3 Readers' comments