The city’s celebrated Victorian pleasure gardens have reopened after a £28.3m revamp – and decades of drama and indecision, writes Elizabeth Hopkirk

The future of Aberdeen’s celebrated Union Terrace Gardens has been a preoccupation of the local newspaper since the 1950s. By the early years of this century the saga had begun making headlines in Building Design as a string of new visions for the Victorian city centre park, some quite outlandish, were proposed and then ditched. Eventually the tale caught the attention of the national papers.

There’s enough drama and strong local feeling that it’s not totally absurd to suggest the story could one day become the subject of an entertaining open air production in the gardens themselves. The cast of characters includes jilted architects, a snubbed billionaire and a vindicated pop star. As it happens, the natural stage at the bottom of the sunken gardens has finally been turfed after an on-off sub-plot, while conveniently raked seating has been installed up the zig-zag paths.

Just before Christmas 2022, BD and the Press & Journal were able to report that the gardens had reopened after a £28.3m revamp by LDA Design.

It was a “soft launch” given the time of year and the amount of planting yet to bed in – as well as a reflection of political jitters – so it seemed fair to wait till summer before reviewing the project. BD visited “UTG” on a Monday morning in late June as heavy rain gave way to sunshine and Aberdeen’s trademark granite was at its sparkling best. Only one other person was in the gardens when we arrived and he was reluctant to share his opinion. “Where do you start?” he glowered and stalked off.

Let’s start with some history.

Union Terrace Gardens has been a green lung at the heart of the Granite City since 1879, when 18th-century linen bleaching grounds were turned into a 2.5-acre municipal park by architect James Matthews (after four years of dithering by the council; plenty more of that to come). They opened to a fanfare, with the band of Gordon’s Hospital playing a “selection of pleasing airs”.

The Den Burn, the river from which Aberdeen takes its name, carved a steep north-south valley through what became the city centre, defining its topography to this day. It gives the park its dramatic character but also its biggest challenges: how to connect the sunken space to the surrounding streets and how to stop the bottom from becoming off-puttingly overshadowed.

The Den was culverted in the 1840s to make way for the railway which still runs along the base of the gardens beside a dual carriageway, Denburn Road, together forming an impregnable barrier along the eastern perimeter. This is a shame since without them there could be level access to the “lower gardens” here.

UTG is still known as Trainie Park by older inhabitants who recall the thrill of watching steam engines. The big architectural landmark on this side is a listed brick spire, all that remains of Archibald Simpson’s Triple Kirks (three churches with a shared spire). It has recently been hemmed in by unsympathetic student flats designed by local practice Halliday Fraser Munro.

The gardens’ north, south and western edges are some 14m higher than the eastern side. This is the level of most of the city including Union Street, the historic shopping street, which runs across the southern end of the gardens as a bridge – at 40m, the largest single-span granite bridge in the world, decorated with “wee leopards” from Aberdeen’s coat of arms.

>> Also read: Union Terrace Gardens likely to be scrapped, says Aberdeen leader

At the opposite end, the north is bounded by another bridge, Rosemount Viaduct, and has the gardens’ grandest backdrop: an imposing civic trio of library, church and His Majesty’s Theatre. Aberdeen’s three graces if you will, but known locally as Education, Salvation and Damnation. Just to the east is Aberdeen Art Gallery, recently extended by Hoskins.

Finally, the long western edge is bounded by Union Terrace and its more modest commercial buildings, also in granite. This road is built over a series of arcades which are a feature of the gardens. For many years they were boarded up but have now been fitted out for business or community use. This is one of many welcome improvements. But before we get to the main act, it’s time for a little melodrama.

In their heyday the gardens were the city’s pride and joy, a place where the great and the good mixed with ordinary folk while strolling among the decorative municipal planting. There were dances, a bandstand and giant draughts boards. In the 1950s there was talk of extending the gardens over the railway line. In the 1960s and 70s the gardens, with their planted coat of arms and immaculate lawns, were a key part of the city’s habitual Britain in Bloom victories. Eventually the organisers asked Aberdeen to stop entering to give others a chance.

But by the 1980s decline and notoriety had set in. Large-scale concerts and beer festivals ruined the grass. The trees had grown so large they screened the activities of ne’er-do-wells. Few people ventured in after dark and images of drug users shooting up in broad daylight appeared in the national papers. Something had to be done.

A few ideas were mooted. Then in 2006 the emerging London practice Brisac Gonzalez was appointed to design a 3,200sq m arts centre in the gardens for local client Peacock Visual Arts. Planning was granted in 2007 and the £13m project was all set. Praised by Architecture + Design Scotland, its supporters said it would rejuvenate the gardens and position Aberdeen as one of northern Europe’s great cultural cities.

But then local oil and fishing tycoon Sir Ian Wood offered the council £50m to back his far more ambitious and expensive proposal to raise the gardens to street level and create a civic square over a subterranean shopping centre. Initial designs by Halliday Fraser Munro with landscaping by Martha Schwartz were billed as a cross between an Italian piazza and Central Park. Writing in BD, Owen Hatherley scornfully asked: “Is there anything more provincial than that statement? We could be a great Scottish city, but instead we’ll settle for a crap version of somewhere else.”

The £140m City Garden Project was hugely divisive, with artists and those objecting to the loss of such a significant part of the city’s heritage among more than 4,000 people who signed a petition against it. Local hero Annie Lennox, one half of the Eurythmics, dubbed it “architectural vandalism”.

Nonetheless councillors threw their support behind Sir Ian’s vision. A disappointed Edgar Gonzalez offered to draw up a compromise but eventually had to concede his arts centre was dead, saying: “This fiasco has left a very bitter taste in my mouth as it seems that one man’s whim along with £50m backing is more important to the local elected officials than the public’s opinion.”

An international design competition was announced. Organiser Malcolm Reading suggested a public contest could help heal the rift. Scottish Enterprise asked RIAS for help – and was promptly shopped by its chairman Neil Baxter for wanting an international winner and for “insulting indigenous talent”. Foster & Partners, Snohetta, Niall McLaughlin, Mecanoo and West 8 were among the finalists.

In January 2012 a winner was declared: Diller Scofidio & Renfro and Keppie’s Granite Web. Implausibly, this proposed building a cat’s cradle of granite and grass bridges over a gleaming undercroft that even in a city blessed with more sunshine than Aberdeen would have struggled not to become a gloomy locus of anti-social behaviour.

Stuart MacDonald, head of Gray’s School of Art, dismissed the contest as a “knee-jerk reaction” to Dundee’s V&A competition, won by Kengo Kuma. There were angry demonstrations and two public polls. Both were close but in the first the public voted against the City Garden Project, only to be ignored by the council. The second found marginally in favour (moral: keep trying till you get the answer you want) but by then the writing was on the wall.

Local elections saw the ruling party thrown out. The new administration, which pledged to scrap “vanity projects”, formally killed off the plans in August 2012. Once again it was a narrow vote: 20:22 with one abstention and there was some last-minute drama from two of our favourite protagonists.

Pantomime villain Sir Ian offered to underwrite more of the bill, while real-life diva Lennox took to Facebook to hammer in a nail. The Granite Web was “another dog’s dinner of crap concrete development, ravaging the only authentic, historical green space in the city centre”, she wrote.

As one leading Scottish architect had predicted months before: “Not a single significant public or privately financed building has been built in Aberdeen for 40 years. The council is incredibly indecisive. The risk is they waste time on this massive project… and then it never happens.”

And so it came to pass.

Back to the drawing board. In 2015, the council approved a 25-year city centre masterplan containing a much more modest £17m “revitalisation”. The following year LDA Design was appointed, reportedly seeing off competition from nearly a dozen rivals including Fosters. In 2017 their £20m proposals won outline planning – after another knife-edge vote – with completion set for 2019.

When detailed planning was granted in 2018 the budget had become £22m. A year after that work had still not started and was now slated to finish in 2021. The timeline slipped further after a number of delays caused partly by the pandemic and supply chain issues.

In a plot twist in 2021 the police were called when it emerged that granite slabs from the gardens had been found piled up in someone’s back yard. They were later returned and the investigation dropped. More bad publicity followed when local trade unions criticised the standard of work. The council was forced to issue a statement that the “flush lime pointing… employs a mortar mix approved under Listed Building Consent, complies with modern conservation practice, and is being overseen by a member of RIAS”.

Also read: Years of uncertainty over as £22m Aberdeen project set for OK

A soft opening was all set for April 2022 but was pulled on the morning of the ceremony. The Press & Journal, whose staff documented the project’s travails on an almost daily basis from their offices overlooking the site, questioned why no one had thought to cancel it earlier given the ongoing presence of JCBs and mud. Reporters later discovered that a commemorative plaque, etched with the date of the aborted opening and subsequently binned, cost the taxpayer £265.

Nonetheless, eight months later the hoardings came down and the public were able to assess what was now a £28.3m project. They were underwhelmed. It didn’t help that the central lawn was still just soil, a pragmatic decision taken to wait till after a festival in February.

By May the earth was still bare and a prankster raised a giggle with signs announcing: “Scotland’s first grassless park”, “Mud is the new grass” and “The emperor’s new grass”. They were quickly removed but at the time of BD’s visit there was still no grass. The turf finally went down at the end of June and will be protectively roped off for a while longer.

Given all that, it’s no surprise that the man in the gardens approached by BD didn’t know where to begin. Others were happier to talk, with views ranging from positive to cynical and some too weary to have visited yet. There are some legitimate grumbles like the felling of mature trees, the somewhat incongruous design of three commercial pavilions and the sheer scale and disruption of a project people were expecting to be a modest revamp. But Aberdonians admit they like a moan and the truth is that UTG is – finally – a nice place to be again.

What did the project involve?

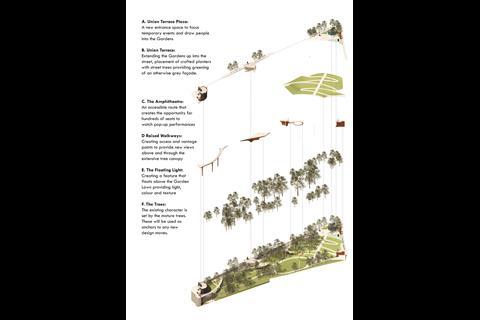

The most dramatic changes are the loss of trees, the introduction of step-free access and the pavilions. The designers say there has been a net gain in trees, including some larger specimens, while a few of the originals survive. But there is now a lot of sky where two summers ago there were leafy crowns.

As a result there are clear sightlines through the park as well as viewing platforms and multiple entrances, all of which should encourage people to venture in. At street level the gardens are ringed by a granite balustrade which originally provided only three access points: two dog-leg staircases from Union Terrace and another from the north. Now there is a lift via one of the pavilions and two ramps, as well as the much-enlarged ceremonial staircase and a couple of other sets of steps.

One of the ramps is an 80m long footbridge giving access from the south for the first time, a revolutionary move enabling a genuinely useful north-south route. It slopes down from Union Street, its rather shouty champagne-coloured railings matching the pavilions’ cladding. It passes planted borders and play equipment set in a lurid blue safety surface. For those in a hurry there is also a playful metal chute, the fastest way to the bottom.

The whole corner feels like an invitation to the city to congregate, enjoy the view and contemplate an expedition down into the main gardens

The ramp at the northern end is no less significant. It zigzags round the steep ceremonial staircase, reaching street level near the smallest pavilion, a delightful cafe-bar named Common Sense after the 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment school of philosophy (which could explain why one customer was reading Plato and Kant during our visit).

This north-western corner is one of the most successful parts of the project, creating a gentle threshold between city and garden. The statue of William Wallace which once stood beside a fenced-off patch of grass and trees separated from the gardens by a slip road has been incorporated into the new scheme with an infinity pool round his plinth, granite seating and soft planting.

The road is no more and the ornamental railings have been sliced open. The whole corner feels like an invitation to the city to congregate, enjoy the view and contemplate an expedition down into the main gardens. By mid-morning, families and tourists were happily loitering in the sun and joggers were tackling the steps.

All three pavilions share a design language and have been likened to trams for their distinctive curved glass facades. Their powder-coated metal and bright precast concrete cladding is a bit bling for Aberdeen (where you need good reason to deviate from granite), but light-filled timber interiors and generous views make them pleasant to be inside. The larger two were on the verge of becoming white elephants but have recently been let to a community group and a wine bar operator.

Beneath the southern-most pavilion is the gardens’ original Victorian toilet block, its magnificent B-listed interiors restored and apparently converted for cafe use. Beneath the middle pavilion and a new viewing platform are two obtrusive metal structures cantilevering out from the Union Terrace arcade (whose units remain unoccupied, though one has been converted into new toilets that have yet to open). Unabashedly contemporary, one can only hope these inverted ziggurats are eventually screened by the vegetation that is already beginning to establish itself around them.

Above all, what are needed from modern city centre pleasure gardens are attractive, peaceful and biodiverse places to sit, stroll and play

The fashionably naturalistic planting is another highlight, its soft forms a world away from the municipal flower beds of yore. The site’s steep slopes cascade with 122,000 plants, including ornamental grasses, salvias, hostas, hellebores, foxgloves, poppies and cranesbill, chosen to encourage biodiversity. The terraces also abound with built-in benches, creating an amphitheatre. High above the reduced central lawn – roughly at street level – hangs a giant halo, the most visible part of a new park-wide lighting strategy designed to improve safety while not deterring wildlife.

Setting aside a few duff choices and the painful back story, LDA Design has created a good solution for this important but tricky site, using high-quality materials and planting. The landscaping feels familiar to anyone who has visited its other recent projects like Battersea Power Station and St Mary-le-Strand in central London, which are also being gradually occupied as people discover their charm.

Above all, what are needed from modern city centre pleasure gardens are attractive, peaceful and biodiverse places to sit, stroll and play, as well as clear through-routes to encourage footfall. By that score, LDA Design has succeeded in Aberdeen. This is a scheme that should last the test of time. The headlines may continue – only in June the King caused a stir when he bought the park’s redundant cast iron gates for £500. But, after years of drama, the curtain has come down on an unexpectedly self-effacing star.

>> Also read: Architects urge council to reject demolition of Shell’s former Aberdeen HQ

Project team:

LDA Design

- Lead Consultant for Multidisciplinary Design Team

- Regeneration and Masterplanners

- Landscape Design

- Ecology and Biodiversity

- Community and Stakeholder Engagement

- Heritage, Planning and Listed Building Consent Project Management

Key subconsultants:

Arup

- Civil and Structural Engineering

- Geotechnical Engineering

- MEP

- Bridge Design

- Lighting

Stallan Brand - Architecture and Conservation

Ryden - Project Management / Economic Consultancy

McLeod and Aitken - Cost Consultancy

Beautiful Materials / Rob Mulholland - Public Art

Balfour Beatty - Main Contractor

Ashlea Ltd - Softworks Contractor

No comments yet