Nicholas de Klerk is stimulated and inspired by Ruth Lang’s book on creative reuse

In an ideal world, debate around the re-use and adaptation of existing buildings would already be settled. With an exponentially expanding and urbanising population, finite resources and an increasing frequency of extreme weather events driven by climate change, it is clear that the planet we share is in peril and the environmental impact of our day-to-day activities must figure in the decisions we make about them.

Construction, which accounts for over a third of global carbon emissions, is an obvious target for improvement. Neatly positioned within this is the issue of extending the lifespan of existing buildings which have, on the face of it, outlived their immediate usefulness.

It is worth first dispensing with the old canard that working within the constraints of existing buildings might present, as Lang cites, a ‘limitation to creative freedom’. This notion lays bare one of the founding conceits of architecture as a contemporary discipline – that it somehow rests on individual creative genius, when even those that propagate this myth know that the opposite is true.

For me this attitude represents nothing less than a failure of the imagination – something which is amply demonstrated by the collection of projects in this book.

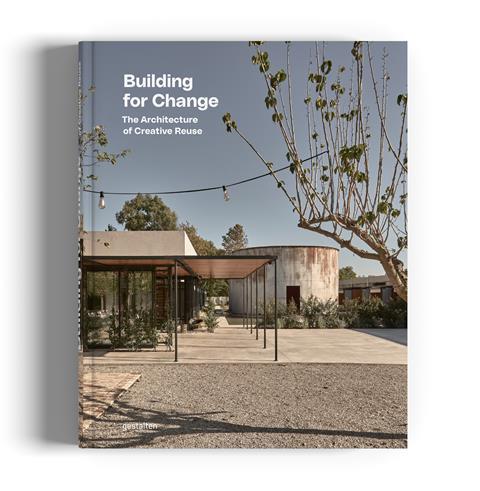

Lang’s 256-page, lavishly illustrated volume, published in August, frames the debate around adaptive re-use using six separate ‘strategies’, supported by a series of building case studies. Underpinning this examination is a simple yet fundamental shift in perception that begins to consider existing building stock as a resource in and of itself. This has the potential to both reduce the quantum of resource extraction demanded by materials for new construction and the amount of waste ordinarily sent to landfill following demolition.

The strategies include assessing and overcoming perceived and actual obstacles to re-use, strategies for implementation, responding to shifting patterns of use at the scale of both cities and buildings, considering material re-use (specifically from a procurement and programming perspective), whole site re-use and lastly design for disassembly and re-use. This organises the book and lends it a loose (there is an introduction but no formal conclusion), discursive structure that enables and perhaps even encourages the reader to dip in and out.

Each case study is brief yet detailed enough to offer meaningful insight, and a map to further investigation or research. Brandlhuber+’s Antivilla repurposes a post-war lingerie factory into living accommodation and studios and instead of fully insulating the structure, sets up a series of climatic ‘zones’ within the building. This functions in principle in the way in which insulation – as a tactic – might, in effect reducing the area of the building that requires heating during the colder months.

The primary obstacle to this approach was in complying with building regulations which led to the installation of a geothermal underfloor heating system. With the caveat that this project was designed for the architect’s own use, and is indeed a private house, this project suggests a way of thinking that could be developed to resolve some of the contradictions inherent in bringing historic buildings in line with current regulatory requirements.

Flores & Prats’ Sala Beckett in Barcelona converts a disused cooperative grocery and community centre into a theatre and drama school. It took the opportunity to undertake a fine-grained survey of the existing fabric, cataloguing doors and windows, mosaic tiles and wall mouldings, setting out a strategy for their removal, repair and reintegration into the completed project.

This approach is more evolution than conversion, reimagining the building into its new use, and the architect as custodian. It creates a rich palimpsest of material and cultural references and sets up a dialogue between retained, repurposed and new elements and invites those with memories of the building as it was into a relationship with the building as it is now. Sala Beckett offers an unequivocal riposte to those that imagine their creativity is somehow constrained by working with existing structures.

The book covers projects with a wide geographic reach with only three of the thirty-five projects located in the UK. We already know that eighty percent of the buildings that will exist in 2050, the putative date by which the UK is to have achieved its zero-carbon target, already exist. Lang’s book comes as a timeous insertion into this debate, offering both rigour and imagination, daring the profession to do more with less.

Postscript

Building for Change – The Architecture of Creative Reuse by Ruth Lang is published by Gestalten

Nicholas de Klerk is the founding director of Translation Architecture

No comments yet