Tom Dollard’s book is both a useful technical reference point and an inspiring guide to the future of energy efficient construction, writes Tony McIntyre

In 2014, the public/private partnership Zero Carbon Hub identified three main problems in house construction: lack of knowledge and skills, unclear allocation of responsibility and inadequate communication of information. Their study of 300 new homes showed that all failed to match their intended performance, most by over 50%.

Tom Dollard, partner for sustainability and innovation at Pollard Thomas Edwards, a practice specialising in domestic and community architecture, is in ideal position to analyse current practice on the ground and to propose remedies to this significant shortfall.

What he provides in response is an up-to-date detailing manual, the purpose of which is to narrow that performance gap: the gap between predicted and as-built energy performance. As such it could hardly be bettered.

I look forward to the day when the ratio of natural materials to ‘traditional’ construction is more like 1:1

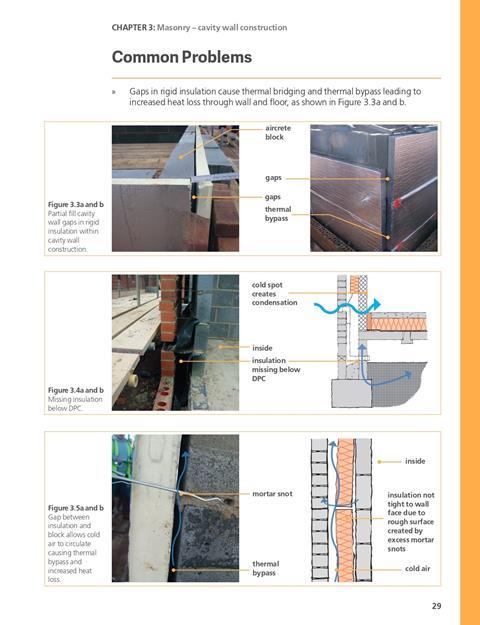

Chapters cover the basics of thermally efficient detailing and the principal construction methods in general use: masonry, concrete, timber framing and so forth. Excellent line drawings illustrate ‘good practice’, and there are clear photographs of actual construction projects, some showing faults, others correct detailing.

This revised edition adds a welcome chapter on natural building materials, including clay blocks, hempcrete, rammed earth, cork, and straw. They make a good chapter, but one would like to see so much more in this direction.

I look forward to the day when the ratio of natural materials to ‘traditional’ construction is more like 1:1. Inverted commas for ‘traditional’ because natural materials are really more traditional than so much of what it illustrated in the first 7 chapters. As these case studies show, trying to make a typical cavity wall meet thermal performance standards is a task fraught with difficulty.

In so many ways these forms of construction are barely capable of being made to conform

There are really two kinds of ‘traditional’ construction. One, which might be called ‘old traditional’, involves cruck framing, wattle and daub, cob, brick and tile, solid stone and the like – some better than others at thermal performance. The other might be called ‘modern traditional” – cavity wall, concrete floors, flat roofing.

Devising ways to make this second group come up to scratch is the main subject of this book. And my word, is this a convoluted process. In so many ways these forms of construction are barely capable of being made to conform, requiring a degree of precision and attention to detail that seems more suited to factory construction than on-site work.

One need only look at the growing industry of new-build quality inspectors, whose job involves snagging newly completed and signed-off houses. It isn’t just a case of finding careless detailing and construction, but often as not intentional deceit – fake weep holes in brickwork, fake expansion joints, missing fire barriers.

Shoehorning compliant detailing into outdated technologies using an under-skilled and cheeseparing workforce is unlikely to be a long term solution. Yes, education and a tight inspection regime, but who is going to organise and pay for those in present circumstances?

There are so many alternatives in development. Outside Barcelona, the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia has just completed the TOVA mud house, made largely with a Wasp 3D printer.

Built examples of ashcrete, ferrock, mycelium, and other materials are increasing and also deserve attention. This book would provide and excellent medium for their promotion. (Though one of my favourite adobe buildings was built as long ago as 1937 by Vernon De Mars and Burton Cairns in Arizona – a co-operative farm community sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

Clearly construction will have to move away from its heavy dependency on ‘modern traditional’ and towards innovative methods, based in some ways on ‘old traditional’ materials, if not constructional details. We are some way off abandoning the constructional nightmare of the cavity wall, but I look forward to future editions of this book where the proportion of chapters dedicated to alternative material becomes ever greater.

Postscript

Designed to Perform: An Illustrated Guide to Delivering Energy Efficient Homes, 2nd Edition, by Tom Dollard, RIBA Publishing

No comments yet