What’s happening at the Balfron has infuriated many but don’t be too quick to criticise, cautions Owen Hopkins. The alternative for many brutalist gems is oblivion

Even 10 years ago to profess mild regard, let alone enthusiasm, for brutalism would be met with bewilderment, a question mark quite possibly raised over one’s mental state. Everyone knew that brutalism was a step too far – even hardened modernists who saw its bloodymindedness as having alienated the public. In the words of one distinguished architect, alas no longer with us, brutalism had “irrevocably set back the course of modern architecture in Britain”.

How then has brutalism now become fashionable? And why has this much-maligned style attained the legitimacy of support from such venerable institutions as the National Trust and my old employer the Royal Academy? The answers, as I begin to explore in my latest book Lost Futures, are as complex and arguably as reflective of the politics of our current moment as the ideas and contexts that led to its creation.

Part of brutalism’s revival is simply the wheel of taste turning, and the echoes of that frisson of excitement for those early pioneers who professed admiration for a style of architecture that was shunned by the mainstream. Yet what had caused brutalism to be so vilified was not solely the trajectory of fashion. Its demonisation can be traced to the late 1970s and 1980s and the broader the backlash against modern architecture – especially housing – and the values that had sustained it in the post-war years. Brutalism stood as the most extreme example of what was under ideological attack.

Thus, for those looking today for alternatives to the political consensus forged during those years, brutalism is an obvious cause célèbre. To align oneself with brutalism is a way of endorsing the ideals it was vilified for, but in which many see huge value: state action; the belief in the collective ability to build a better world; the very idea of progress. For the generation born in the 1980s and after, who were not indoctrinated during the backlash against modernism, these ideals and their architectural manifestations have major appeal. Amid a deepening housing crisis, brutalist architecture – which after all was mostly housing – offers a very powerful alternative to the status quo.

Yet one does not have to be a paid-up member of the political left to be a fan of brutalism. It has gone mainstream through a proliferation of blogs, Twitter feeds, and coffee table books, not to mention mugs, plates and tea towels. Brutalism’s strikingly abstract geometric forms are readily distilled into images ideally suited to the hyper-reality of social media. In the online world, brutalism’s popularity has gone hand in hand with the phenomenon of “virtue-signalling” whereby what you “like” or retweet is part of an idealised construction of your self-image. To share a photo of brutalism is to loosely align yourself with its residual outsider status – whether political or cultural – without ever having to get your hands dirty by visiting a brutalist building or engaging with anything as radical as housing activism, for instance.

But before we get too carried away criticising the digital appropriation of brutalism and the draining of its politics, we should remember that the “imagistic” qualities of this architecture were one of its intended defining characteristics. In addition, while brutalism has been adopted by leftists, its actual politics are rather more complex: simultaneously part of a doubling-down on modernism’s early radicalism and transformative sprit, yet at the same time hugely interested in popular culture and consumerism.

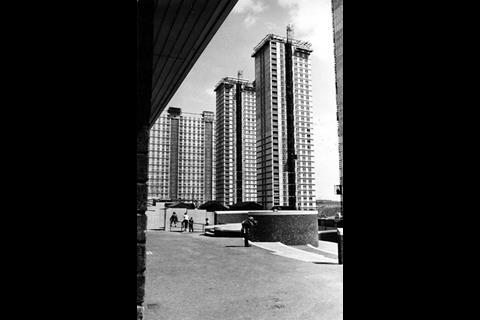

However we analyse the revival of interest in brutalism, its buildings – and post-war architecture generally – are being lost at a dizzying rate. Part of this is simply a consequence of the natural life-cycle of buildings. To the more politically inclined, however, it is indicative of an ideological move to eradicate the physical evidence of a social democratic moment in the nation’s politics, with the destruction of numerous housing estates an attempt to “socially cleanse” the poor from our inner cities. While rejecting the frankly offensive hyperbole equating these actions with “ethnic-cleansing”, and the London-centric nature of most of these arguments that rarely bother to consider the world outside the capital, there is something in this view, though it is rather more complex and contradictory than usually admitted.

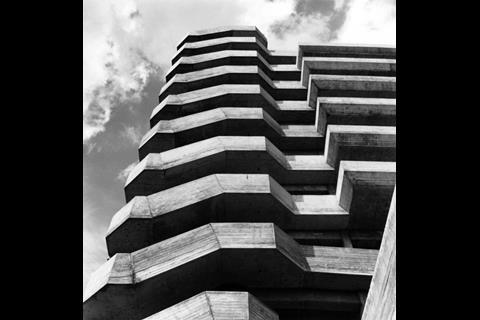

At the same time as we are witnessing the destruction of numerous brutalist housing estates – most notably the Heygate at Elephant & Castle, but many others too, including the currently gravely threatened Central Hill in Crystal Palace – we are also seeing brutalism’s fashionability exploited by developers. The most notorious example is Ernő Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower in Poplar which is being refurbished and then sold off as luxury flats. Admittedly this is to pay for the refurbishment of the broader estate in which Balfron lies, but the symbolism is clear: a once-powerful emblem of the welfare state now rendered just another luxury tower. The tactics employed by the developer are pretty cynical too: moving artists into the decanted flats to enact a kind of turbo-charged gentrification before the arrival of the gentrifiers wanting easy access to their bankers’ jobs at Canary Wharf.

Several commentators have questioned the role of these artists in helping to serve up the tower to the property speculators, with one notable figure, who has made his name as one of brutalism’s main cheerleaders, arguing that “this stuff [brutalist architecture] isn’t neutral … you have to think about the forces you’re aligning with”. But given the way they are being all but driven out of central London, even out of the city itself, who can blame artists for taking whatever is offered to them.

The upside of all this has been the preservation of the building and the increasing attention turned to preserving brutalism more broadly – which should not be ignored. Even when Balfron Tower is occupied by affluent workers from Canary Wharf, the socially progressive ideals that are inscribed into the configuration of its flats, its communal spaces and its elevation – that this was a building intended for the betterment of everyone – cannot be erased.

It may be possible to appropriate the image of brutalism, but the buildings themselves resist; and to say they do not is to underestimate this architecture’s power. As I argue in Lost Futures, the gentrification of brutalism may indicate that the political ideals some saw in it are no longer considered to pose any threat to the politico-economic status-quo. Yet by helping preserve its buildings gentrification has also kept visible the radical alternatives they present for the future.

Postscript

Lost Futures: The Disappearing Architecture of Post-War Britain by Owen Hopkins is published by the Royal Academy of Arts, £12.95 hardback. The associated display and events programme, Futures Found, at the Royal Academy of Arts is on until September 18.

No comments yet