The RIBA president and WW+P co-founder talks to Tom Lowe about the threat AI poses to the architecture profession, his plans for increasing architects’ pay and his award-winning stage play about Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo

“In my mind, Richard Rogers is more like Leonardo and Norman is more like Michelangelo,” says Chris Williamson. He is talking about his award-winning stage play, Legacy, which is about the rivalry between the two renaissance masters. It is also about rivalry in general, particularly when it concerns great artists – including Rogers and Foster.

Williamson started writing the two-hour historical drama during the covid lockdown, and in February sent it to the Script Awards in Los Angeles, where it won Best Stage Play. Later that month it was named Best Feature Script at the Cannes Arts Film Festival, an online competition dedicated to promoting independent film.

Now the WW+P co-founder has been elected RIBA president, beginning his term in September this year. His successful foray into playwriting makes him one of the few high-profile architects to receive recognition for work outside the architecture and design professions. He joins a small circle including former RIBA president Maxwell Hutchinson, who composed three musicals and a requiem mass.

Could this be the start of a late career reinvention for Williamson? “I’m not a writer,” the 69-year-old insists. “I love writing. I love reading; I’m a member of two book clubs. So I’ve enjoyed the writing, but you’re never sure if it’s any good. But when it wins a prize, you think: ah… this might be good.”

The story, set during the early 16th century, was inspired by how artistic ambition can be driven not just by competition with a rival but by a desire to be remembered in a certain way, hence the title. “The older you get, the more you’re aware of how people think of themselves and their legacy,” Williamson says, “which is something that I’m not at all interested in personally, but I can see why it consumes people.”

In terms of who could potentially play the leads, there are some intriguing possibilities. The manuscript has been read by none other than Game of Thrones actor Charles Dance, who Williamson happened to be sat next to at an alumni dinner – also attended by Make founder Ken Shuttleworth – for former Leicester De Montfort University students. Dance, who studied photography at the university, “started chatting to me about my play, because I couldn’t think of anything else to talk to him about,” Williamson recalls. “He was genuinely interested in it.”

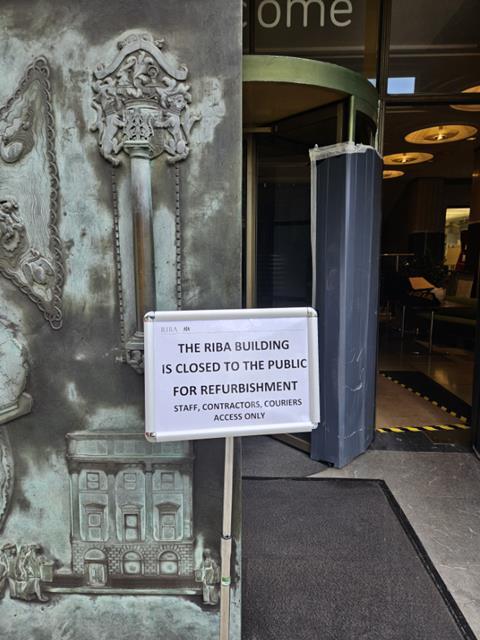

Divided opinions: RIBA’s £85m headquarters transformation

Building Design is talking to Williamson not in the RIBA’s famous art deco headquarters, the grade II*-listed 66 Portland Place in Marylebone, but in an office next door at the rather more humdrum 76 Portland Place. The institute has just embarked on an ambitious – and mildly controversial – £85m transformation as part of past president Simon Allford’s House of Architecture programme, with £60m to be spent on upgrading its central London base. Many of the institution’s fee-paying members have doubted the necessity of spending so much on a project consisting of little more than adding a cafe and upgrading the building’s services – although anyone who has used the building’s ancient and panic-inducingly small lifts may disagree.

Williamson himself questioned the price tag in his campaign for president. “I thought it was a lot of money to spend,” he admits. He had sent his manifesto to Norman Foster, who, according to Williamson, wrote back and said that he agreed with everything in it but stressed the need for RIBA to have a physical presence.

I love the building… I have a sort of emotional attachment to it

Williamson is now a convert, describing the work as “high value but good value”. There is also a sense of urgency in the organisation to stay relevant – with its traditional role seemingly encroached upon by the Architects Registration Board (Arb) and its purpose increasingly questioned by its members. The latest example is the institute’s recent logo rebrand.

“I think politically and from a reputational point of view, you need a brilliant building, and unfortunately, it’s not a brilliant building at the moment. So I think that it is important that it gets done,” Williamson says.

RIBA staff have been working remotely since the refurbishment began in the summer but will soon move into offices at the British Medical Association. With work at 66 Portland Place set to take at least two years, the length of a RIBA presidential term, Williamson is likely to be the first president since the building’s construction in the 1930s to never work there. “It’s a pity,” he admits, “because I love the building… I have a sort of emotional attachment to it.”

Building on 40 years of practice

It was at 66 Portland Place where Williamson really found his feet as an architect and business owner. In 1985 he and Andrew Weston were selected for RIBA’s 40 under 40 exhibition, along with several other future big hitters including Bob Allies and Amanda Levete. At the time, Williamson had been working at Michael Hopkins and Weston was at Richard Rogers, and the two had been working in the evenings to enter competitions under their own names. Michael Manser, the president at the time, suggested the pair set up their own practice.

“Because we weren’t earning that much, we thought all we’ve got to do is to earn the same salary so we may as well give it a go,” Williamson recalls. “So I have a lot of emotional attachment to the RIBA because of that and the encouragement that they gave us as young architects.

“That’s why I wanted to do this job,” he says, “to make sure that young architects now have the same opportunity and feel the same sort of allegiance to RIBA in order to develop their own career.” WW+P, the practice he and Weston founded later that year, now employs more than 250 people across five offices, in London, Manchester, Melbourne, Sydney and Toronto.

Architecture wasn’t something that was suggested to me when I was a kid. It’s not something that’s suggested to working-class kids

Williamson expressed this sentiment in his speech at the recent Stirling Prize ceremony, his first big outing as president. Paying tribute to Nicholas Grimshaw and Terry Farrell, who both died in September, he remembered the support both architects had given to him when he and Weston were starting out. “I was incredibly fortunate to have spent time with them both,” he told guests at the Camden Roundhouse on 16 October.

Farrell had given the pair a job working on a rail station in Vasteras in Sweden, while Grimshaw had accepted an invitation from Williamson to speak at De Montfort University during Williamson’s time there as a student. “He arrived off the train from London with a green plastic briefcase, de rigeur among architects at the time, containing a Kodak carousel, notebook and an apple pie for the journey home,” Williamson recalls.

Representing the entire profession

The anecdote also underlines how well connected Williamson is as an architect in the fifth decade of his career. In this respect he is the polar opposite of Muyiwa Oki, his predecessor as president, the youngest person to ever hold the role, the first black president and a salaried architect working at Mace. If Oki was seen by members as a reaction against the RIBA tradition of electing high-profile architects and practice leaders as president, Williamson risks being a return to type.

>> Also read: As his RIBA presidency ends, Muyiwa Oki reflects on milestones and unfinished business

But Williamson insists he shares many of the same goals as Oki, despite his more elevated position in the profession. “I think he’s been great, a great face for the profession,” he says of Oki. Getting more people from diverse backgrounds interested in the profession was one of Oki’s key motivations during his tenure, and it is something that Williamson, who grew up in a working-class community in Derbyshire, would like to continue. “It’s really important to me because architecture wasn’t something that was suggested to me when I was a kid. It’s not something that’s suggested to working-class kids.”

Where the two might differ is on Williamson’s goal of supporting the entire profession rather than a focus on under-represented groups. “I don’t want to just represent young workers or the salaried architects,” he says. “We need to look at the big practices, the small practices, the specialist practices. I need to represent everybody.”

Taking a stand on controversial issues

In this respect Williamson may appear slightly less inclined towards the radical wing of the profession than was his predecessor, who was originally put forward for the role by a student campaign group called the Future Architects Front on a platform of progressive change. As president, Williamson is also expected to represent the profession in commenting on controversial issues. What does he think about architects arrested under the Terrorism Act for protesting in support of Palestine Action, a proscribed terrorist group?

I love freedom of speech. You’ve got to be able to have a right to protest

“My honest opinion”, he says carefully, after a long pause, “is that I love freedom of speech. You’ve got to be able to have a right to protest. I don’t think you should support terrorist groups. Whether they should be a proscribed terrorist group, that’s another debate, but I agree with the right to protest, peacefully.”

Hundreds of people, including Manalo & White commercial manager Steve Fox, were arrested at protests during the summer and early autumn for holding signs saying “I support Palestine Action”. It is not something Williamson would have done.

“The clever people were holding up placards saying ‘I don’t support Palestine inaction’, which I thought was quite clever, and they don’t get arrested because they’re not supporting a terrorist group. If I was protesting, that’s probably the way that I would have done it.”

Tackling low pay through specialist skills

Williamson is not known for shying away from giving his opinion on divisive issues. Last year he found himself in hot water after penning a blog post defending architectural competitions, which are seen by many in the profession as exploitative. The 600-word post received a largely negative response from social media users, with one architect describing it as “tone deaf”.

“I don’t know why,” says Williamson. “What I was saying was, I think for young architects, competitions are a great way of being able to show what you can do, as long as competitions are well run.”

Specialist knowledge gives you an advantage when it comes to getting paid better

But getting embroiled in online spats is not how Williamson wants to spend his two-year term. His focus is on education and lifelong learning, something which he believes is essential to increasing architects’ salaries. “Most architects are concerned about low pay and low fees,” he says. “To me, lifelong learning is a way of proving that you have got specialist knowledge, and usually specialist knowledge gives you an advantage when it comes to getting paid better.”

He wants to enable the RIBA to become seen more as a provider of specialist qualifications than as a member organisation, by making its CPD “less product-based and more specialist-based”. Allied to this is his goal of convincing politicians to turn to architects for these expert and specialist skills. “I think, a lot of the time, politicians… think we’re generalists, and if they think of us at all, they don’t necessarily ask for our opinion about power, about infrastructure, about hospitals, about schools – where we have some of the best people, the best designers that have spent their whole lives working in practices with great specialist knowledge of those things.”

He adds: “I think everybody wants to be paid more, but we all have to do what we need to do to make that happen or make that more likely. So I think we need to get better, and then we can get paid more.”

AI threatens to make ‘everybody an architect’

These ambitions come against the backdrop of arguably the most serious threat to the architecture profession in living memory, the rise of AI. With AI already able to design entire projects of comparable quality to those made by humans, at greater speed and at a fraction of the cost, and with the sophistication of the technology increasing at an alarming pace, is the profession looking at the potential extinction of the architect in the traditional sense within the next decade?

Anybody that can use a computer will be able to describe what they want and generate designs. It’s already happening

“I think it is a threat to the profession in that I would imagine in five years’ time, 10 years’ time, everybody could be an architect. Anybody that can use a computer will be able to describe what they want and generate designs. It’s already happening,” Williamson says. Architects are, he says, currently divided between those who are embracing AI and those who are “burying their heads in the sand and hoping it will go away”.

All creative professions are now having to dig deeper in search of skills that set them apart from computers. How will architecture survive? “I think we will have to adapt. We will have to change, but I think it’s something that we should be talking about and not ignoring, because it is going to happen quite quickly.”

The answer, Williamson believes, is focusing on the human needs of paying clients, the creative dialogue between client and architect, and the human touch needed in certain types of schemes, such as Maggie’s Centres. But while it is likely that some buildings will always call for human-led design, the stark reality of this is that it could mean a drastic reduction in the amount of work for human architects in an already oversupplied sector.

“I guess it’s like vinyl records,” Williamson says. “Everybody thought they were redundant… but people actually like the sound and they like the experience.” With vinyl sales not exactly what they used to be, this might not be the most reassuring analogy.

Williamson has started his presidency at a dicey time for architects, with the sector’s longstanding challenges of downward fee pressure and shrinking project responsibilities compounded by a chronically sluggish economy and now the rise of AI. With change coming at a breakneck pace and its consequences hard to predict, it is uncertain what state the profession will be in when Williamson finishes his term in two years’ time and the RIBA moves back into its refurbished headquarters. In this context, he might be right to focus on education and specialist skills – they could, bar a switch to writing stage plays, be the sector’s best available lifeline.

Chris Willamson’s CV

- September 2025 Inaugurated as 81st RIBA president

- July 2025 Elected RIBA president

- February 2025 Legacy wins Best Feature Script at Cannes Arts Film Festival and Best Stage Play at the Script Awards Los Angeles

- May 2024 Launches campaign for RIBA president

- 2022 WW+P’s Paddington Elizabeth line station completes

- 2022 WW+P acquired by Egis Partners

- 2020 Started writing Legacy

- 2016 WW+P opens first overseas office in Melbourne

- 1999 London Bridge Jubilee line extension completes

- 1985 Founding partner, Weston Williamson + Partners

- 1980-1985 Architect, Michael Hopkins Architects

- 1980 Architectural assistant, Welton Beckett Architects New York

1 Readers' comment