Malcolm Fraser Architects has honed its reputation in Edinburgh, but how has its approach translated to creating Work Space, a business incubation centre in Berwick-upon-Tweed?

In the 10 years since the Scottish Poetry Library opened to the public, Malcolm Fraser Architects’ star has moved continuously upwards among the powers-that-be in Edinburgh. The general perception — to a substantial extent articulately promulgated by its eponymous principal — is that this is one firm that has fully absorbed the genius loci handbook and is a safe set of hands when it comes to working within the world heritage sites of the city’s Old and New Towns.

The proof, as they say, is in the pudding, and there can be no argument that Fraser’s office has regularly and consistently delivered, with a range of award-winning projects such as Dance Base, Rick’s Hotel, Dovecot Studios and the Scottish Storytelling Centre, as well as — unlikely as it may seem — a swathe of Pizza Express outlets, all intelligently knitted into the historic fabric of Scotland’s capital.

In a city with around 1,400 resident architects (in a population of half a million), Fraser has worked hard to develop his office, now positioned as one of its leading acts, and by default to instil a reputation among the local press and public alike that he is the Old Town architect.

The big question for others, though, has been whether the architectural approach that has proved so successful for him in Edinburgh can be transferred successfully to other locations — or is it just a very localised variation of the modus operandi Kenneth Frampton many years ago termed “critical regionalism”?

Fraser has of course worked in other cities, notably on the Dance City project in Newcastle as well as the Scottish Ballet headquarters in Glasgow, due for completion next month, but neither location has afforded the kind of opportunity suited to his intensively researched appreciation of place and context.

Intriguingly, it is in an unexpected foray over the border that the beginnings of a similar schema can be discerned: an accretive urban redesign process that tries to look beyond the confines of the single project and considers instead the longer-term potential for wider relationships between the existing and the still-to-be-conceived. There is no question that this is a long game — and one not helped by construction industry stasis — but conversely it is one that may well prove better able than most to offer a framework capable of absorbing ever-changing development imperatives.

Berwick-upon-Tweed, a small town originally laid out in a close pattern interrupted by market squares by Scotland’s King David I in 1126, may seem an unlikely location for further urban design experimentation, but winning a limited interview and tender in 2004 permitted Fraser’s office to explore its potential as a template for similar sized communities throughout the country.

Refreshingly, the solution arrived at was not the now ubiquitous masterplan but a series of what might be better described as orthodontic treatments that were intended to repair or replace rotten parts, fill existing gaps and bring a smile back to the town and the faces of its population.

Certainly, it has been some time since Berwick-upon-Tweed has had the opportunity to smile with confidence, but the Work Space business incubation centre by Fraser’s office that has been open now for several months is a real indication if not of an actual grin, then at least of a town beginning to lift its chin again.

Responding to various studies that had highlighted a decline in business start-ups and VAT registrations, as well as a lack of affordable business space, the project is the first manifestation of a series of regeneration initiatives commissioned by the Berwick-upon-Tweed Borough Council and Northumberland County Council under the flag of Berwick’s Future. The challenge was not straightforward: with a substantial part of the town’s working age population used to commuting by main line train to either Edinburgh or Newcastle, how best to encourage new businesses to set up and stay in the centre of Berwick?

The decision to eschew the convention of an edge-of-town business park and go for a brownfield site was hardly difficult as the borough council already owned the group of neglected and redundant buildings arranged around a medieval yard just off Marygate, the main market street. More importantly, the client understood that the proposed business incubation centre could repair this key piece of the town centre, and with the new activity created by the building, it could potentially catalyse further development around it.

The other critical elements of the project’s brief were that it should be of high quality to attract tenants, and be flexible enough to accommodate the needs of growing businesses. More prosaically, the brief also called for 35 workspaces and information, meeting and conference areas. The defining factor influencing the building’s final form, however, was the client’s desire for the project to recover the medieval yard — and for the centre’s entrance to be positioned on it so as to reconnect the site to the town and provide an enhanced sense of commercial bustle and vitality.

The brief’s urban requirements have been taken a stage further, extending and improving the town’s traditional pattern

Fraser’s design takes the brief’s urban requirements a stage further. The town’s traditional pattern has been extended and improved by opening up the closes into the yard to transform it from its previous enclosed condition. Not only is the link to Marygate made more apparent — the building’s timber-clad entrance is visible from the historic market street — but two new links have been established. The first of these is to the north and towards the site of what is hoped will become a vocational training college; the second links east towards the town library through what is currently a car park, but which potentially could be developed into a new Berwick “yard”.

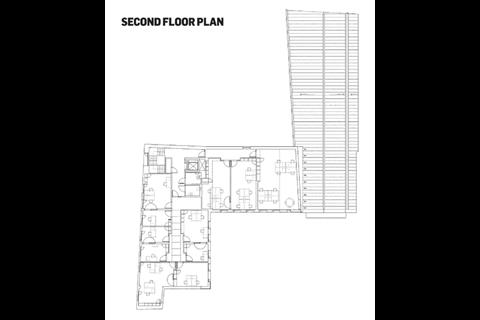

The steel-framed building itself has a Z-shaped plan which effectively follows the footprint of the warehouses previously on the site and, varying from two to three storeys in height, is topped by four parallel pitched roofs that generate a skyline redolent of the town’s existing rich mix of eaves and gables.

Strikingly, the palette of external materials has been limited. On the Walkergate Street face, a lime-based render has been applied above a base of local Doddington stone, while the elevations facing onto Boarding School Yard have vertically fixed, untreated, home-grown larch cladding applied in floor-height tiers.

The same restraint with materials shows itself within the building, the prevailing image being one of timber floors in public areas and plain plastered walls throughout. The business suites themselves are carpeted, but what is more immediately obvious is the variation in their size, layout and volumetric development — no two rooms are the same, some have acoustic doors between them to permit business expansion, while the top floors take advantage of the roofscape interior space to offer grander proportions. There is not a suspended ceiling to be found, even though every unit is wired up to all of the services required to successfully operate and build a business.

Clearly a great deal of thought has gone into the internal planning, and already the hoped-for interaction between tenants is evident, especially in the first floor social area that looks down to the entrance area and out to the yard and the town beyond. Similarly, the conference space at ground floor level opens onto the yard to facilitate external use, and a relationship is now developing between the building’s new business community and the townsfolk themselves.

The centre is not yet and will never be fully occupied — a deliberate decision on the part of the operator, which has a target of 70-80% to ensure future flexibility — but the desired buzz and vitality is there, as well as a very obvious sense of pride in the quality of the premises. And all this has been achieved despite a rigorous value-engineering exercise to keep the project within the £3.75 million budget provided by One North East, the local development agency, and Northern Strategic Partnership, an EU funding programme.

The homework carried out by Fraser’s office in developing this project has been extended to another site in the town. Hide Hill is one of four medieval market squares in Berwick that sit perpendicular to each other and which remain the kernels of the town’s dense urban pattern. Steeply sloping, the hill peters out on its south-east corner in a curiously scaled and now redundant showroom, and it is here that Fraser has proposed a new-build residential development intended not only to bring life back to the area but at street level to introduce one of his long-term clients, Pizza Express, to the town’s commercial streetscape.

The site’s difficult topography has proved advantageous in this instance, allowing Fraser to introduce the complex sectional approach that is so characteristic of his most successful Edinburgh projects and which in this instance promises a new yard within the scheme to add to Berwick’s intricate mix of closes and courts.

Far from being tokenistic, the project’s architecture draws strongly on the town’s unusual history, and as with the Work Space development, it shows no pretensions to be an all-singing, all-dancing foreground building.

Fraser has wisely recognised that other, more obviously civic projects can emerge once the town has regained confidence and purpose. In the meantime, his office has set the bar for new architecture and urban design quality in Berwick, and in doing so has presented an approach that other places — and architects — might in time employ.

Edinburgh’s Old Town architect he may well be, but in Berwick-upon-Tweed Fraser has ably demonstrated that the ideas developed on his home patch can be usefully applied to the regeneration of Britain’s most neglected urban form, the small town.

Postscript

Peter Wilson is an architect and business development director of Edinburgh Napier University’s Centre for Timber Engineering.

To read more Building Studies click here

2 Readers' comments