James Grimley enjoys a new book on Peter Womersley and hopes that it acts as ‘a rallying call to action’ on preserving the architect’s work

In 2014, in a research paper produced as part of the Venice Biennale we asked the question: “who will write the book about Womersley?” Many people could have and almost did, including: Joseph Blackburn, Rebecca Wober, Matthew Wickens and Simon Green - there are a lot of Womersley experts out there. Womersley has attained an almost mythical status amongst architects and rarely has an architectural monograph been more necessary than Neil Jackson’s book. The greatest concentration of Womesley’s buildings are within a 20 minute drive of each other in the Scottish Borders and his buildings shine especially brightly there, where modernism is such a rarity.

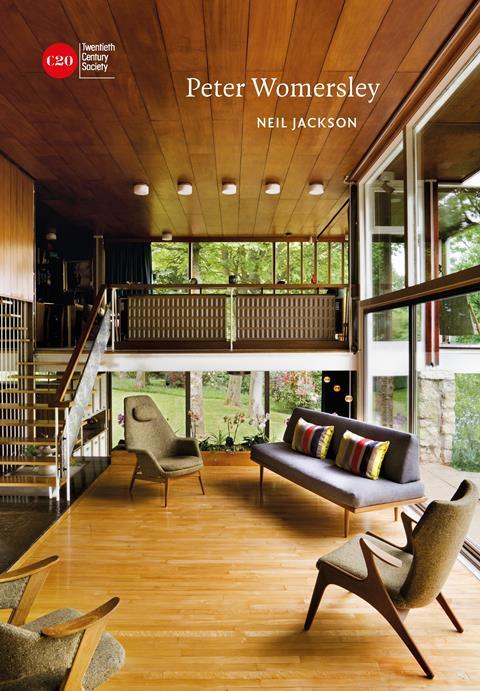

Published by the Liverpool University Press on behalf of Historic England and the Twentieth Century Society, the book is the latest of an important series of monographs on UK architects, some well-known – Edward Cullinen, The Smithsons, and some less familiar - F.X. Velarde, Leonard Mansseh. The book adopts the same format as the rest of the series and is consequently disappointingly small (170 x 240mm x 189 pages), especially compared to some of Jackson’s other books such as his covetable 2019 coffee table sized volume on Pierre Koenig.

Despite its compact volume, (perfect for airports, train journeys and taking on holiday) the monograph is densely packed with drawings and illustrations of very nearly all Womersley’s buildings and projects. And like Jackson’s book on Koenig, the 126 illustrations predominantly show the buildings in their original states - later alterations and ignominies are excluded allowing one to fully appreciate the designs as intended.

The first chapter covers Womesley’s early life, time at the AA and reveals a tendency towards avoiding conventionality (such as not showing up to collect a prize being presented by Frank Lloyd Wright). The following chapters group projects by type – each group roughly corresponding to a period in Womersley’s career. Some buildings don’t quite fit into their assigned chapters such as the Klein Studio being in the ‘Houses’ chapter, but it works as the structural expression of the Studio appears to be the culmination of ideas explored in his later housing designs.

Womersley didn’t theorise about his work, preferring the buildings to do the talking

Jackson has gathered and analysed a huge amount of information. Had there been scope to make the book longer/bigger, one suspects he could have easily filled it with many more enlightening illustrations such as one (not included in the book) he discovered of the original interior of the Galashiels Stand. Because the book is so ambitious in its coverage, omissions are more noticeable – a drawing of Monklands Leisure Centre would have been welcome. But these are minor points as the book presents a large amount of fascinating and previously unpublished material.

Womersley didn’t theorise about his work, preferring the buildings to do the talking and it is a great credit to Jackson that he sticks to biography and refreshingly concise architectural descriptions of the work. The text is clear and easy and the narrative flow of the book is absorbing throughout. Jackson reveals early influences such as the timber framed domestic work of West Coast modernist John Ekin Dinwiddie – who, along with Breuer, Neutra and Ellwood clearly influenced Womersley’s early houses with their posts and beams, full height windows, sunken living areas and unpunctured wall and ceiling planes in finely finished natural materials.

In the chapter on his public buildings – his mid-career works – the timber structures have gone, to be replaced by reinforced concrete, and while the influence of Candela, Kahn and Tange are evident, the works appear more inventive and original. The gravity defying (and now partially restored) Gala Fairydean Rovers Stand, the tapering column walls at the University of Hull Sports Centre and outstanding Klein Studio show Womersley confidently developing his vocabulary. The subtractive compositional methods used in the early houses became more additive. The rigorous grids are still present but so are much more adventurous cantilevers, concrete pushed to the limits of slenderness and a rich structural articulation of elements is evident in much of the work.

The chapter on his later houses shows the same compositional themes with individual spaces being ever more strongly articulated and defined by planes of glass or enclosures of masonry structure. The penultimate chapter looks at Womersley’s time in Hong Kong, first with Marmorek, Womersley and Associates and then with Palmer and Turner where, unfortunately he built very little other than the bronze curtain walled elevations of the St George’s Building for Kadoorie Estates.

It is astonishing that Womersley designed many of his best-known works when he was in his 30s, starting with Farnley Hay when he was only 31 – even more incredible given that national service got in the way of him starting earlier. By the time he designed the Gala Fairydean Stand he was a mere 39.

Biographically, we find that Womersley was a private and sometimes shy individual who both craved and shunned the spotlight. The recollections, memories and anecdotes from the people Jackson interviewed are an engaging and sometimes emotional counterbalance to the works in this fine book.

Following publication of the book, the Twentieth Century Society and Jackson organised a trip to visit many of Womersley’s surviving buildings. It was a great shock to discover that the neglected Klein Studio has started to structurally collapse, with one end of the cantilever beams at first floor level having sheared off and fallen to the ground. Shelley Klein wrote in her memoir – The See Through House: “We’ve got this wonderful cache of extraordinary buildings here in the Borders so we should celebrate and treasure them.”

Jackson’s monograph feels like a rallying call to action. Whilst the Gala Fairydean Rovers Stand has recently been partially restored, and its future is at least somewhat secured, the Studio is now unsafe and in desperate need of rescuing before it becomes another tragic example of Scotland failing to look after its best modern buildings.

>> Also read: Review | Edward Cullinan Architects, by Kenneth Powell

Postscript

Peter Womersley, by Neil Jackson, is published by Historic England in association with Liverpool University Press.

It is part of the Twentieth Century Society’s Twentieth Cenutry Architects series.

James Grimley is chairman of Reiach and Hall and the architect for the Gala Fairydean Rovers Stand restoration project.

No comments yet